Canadian Contingent UNIFIL (CE Newsletter Article)

The Canadian Contingent

United Nations Interim Force In Lebanon (UNIFIL)[1]

LCol G Lackonick, Maj RP Bonner, and MWO G Burtoft

Introduction

"Everything is quiet here. There is shooting all around us but none in our area today. There were four persons killed in the PLO attack at FRENCHBATT last night. I think things will come to a head soon...”

The above diary entry of 3 May 78 made by the CANSIGS Detachment Commander MCpl Mike Forbes located with the Nepalese Battalion in Southern Lebanon portrayed the troubled Lebanese situation which led to Canada's latest contribution to yet another United Nations Peacekeeping effort. During their tour of duty this detachment, located initially at Ebel Es Saqi then Blate, was regularly subjected to indirect and occasional direct exchanges of RPG (Rocket propelled Grenade), MG (Machine Gun), Mortar, and Artillery fire between PLO elements located at Chateau du Beaufort and Christian de facto Forces in the Marjayoun area.

The experience of the Canadian Contingent in Lebanon during the first six-month UN Mandate was viewed by all participants as an effective achievement. Unfortunately, by the time of their withdrawal in early Oct 78, Canadian troops felt a sense of disappointment, as it appeared that there was no clear political solution to Lebanon's complex struggle.

To set the stage for the reader, the first part of this article provides a general overview of the events which precipitated the call for United Nations assistance by the Government of Lebanon and describes the UN deployment during the first mandate. This is followed by the CANSIGS story and is concluded with some observations on this most recent and unique UN operation.

UNIFIL Background

Political System In Lebanon

Before the Civil War. The "National Covenant" of 1943, the year in which Lebanon gained independence from the French mandate, established the Lebanese political system on denominational grounds. Using the current census of the time, the system provided for proportional representation among various religious sects in the Lebanese parliament with the Christians having a slight advantage over the Moslems.

The so-called Christians or Christian Phalangists are spread over four denominations: the Maronites, Greek Orthodox, Greek Catholics, and the Armenian Orthodox. The Maronites play a dominating role and possess the political and economic power in Lebanon. According to the constitution, the Maronites held the position of President of the Republic. Any attempts by other population groups to acquire equality have been rebuffed by the Maronites.

The Moslems comprising the Sunni and Shiite sects as well as the Druze have fought for years for social and political reforms. The first revolt in this connection led to armed conflict during the Lebanon crisis in 1958 in which US Marines were called in to support the Maronite government. The Moslems constitute the largest, but from a military point of view, the weakest population group. Under the constitution this group is assigned the position of Prime Minister and Speaker in Parliament.

The Palestinians. In 1948, Lebanon, like the other Arab states, resisted the UN partition plan for Palestine and went to war against Israel. As the Israelis advanced, the Palestinians fled in thousands. This first wave of refugees was forced to live in refugee camps in Jordan, Gaza, Lebanon, and Syria. A unique Palestinian problem was created. These refugee camps soon developed into centres of anti-Israeli propaganda. From them came the soldiers for the Palestinian commandos and various guerrilla factions. Although the host countries generally supported raids against Israel, these same countries showed little interest in improving the social situation of the refugees.

As the Palestinian military forces grew stronger, they also became a threat to their host countries. In the aftermath of the 1967 war when Israel occupied the West Bank, a second wave of refugees streamed into Jordan. Among these refugees were highly trained commandos who had previous experience in conducting raids into Israel. Soon these commandos turned out to be a threat against Jordan. In Sep 70, King Hussein took military action against the Fedayeen in the so-called "Black September" operation and a third wave of Palestinian commandos poured into Lebanon.

Current estimates place the number of Palestinians in southern Lebanon at about 400,000 strong. They had, in fact, become virtually a state within a state who, with their commando and guerrilla forces, operated from Lebanese territory without any control by the government.

Civil War. By 1975 the main groups dominating the political infighting were the Christian Phalangists, Leftist Moslems, and Palestinians. These were further split into various factions and militia groups and all were heavily armed.

As the activity of the Palestinians was intensified the chances of a confrontation with Israel increased. The Christians felt their position to be threatened and after a number of clashes over the next two years it was only a question of time before a fully armed conflict developed.

After a series of confrontations with the Palestinians, the Christian dominated Lebanese army soon crumbled. In the course of two years the country fell to pieces both politically and socially. During the civil war Christian Phalangists battled a union of Palestinians and Leftist Moslem militias for control of Lebanon only to discover that neither was strong enough to vanquish the other.

At the request of the existing Beirut government, Arab leaders effected a cease-fire and created an Arab Peacekeeping Force (APKF) which moved in and temporarily ended the bloodshed in Nov 76.

Aftermath. The results of the civil war are briefly summary follows:

- none of the political groups achieved their aims;

- the country was completely paralyzed, both socially and politically, and the Lebanese people were more divided than ever before;

- the Christians had not been able to regain the security and domination they wanted;

- the Leftist Moslem factions did not obtain the social and political reform they fought for, but the old system was shaken;

- the Palestinians lost much of their freedom of action, their status and goodwill with the Lebanese people; and

- the price of the tragic war was high. About 40,000 were killed, more than 100,000 wounded and about 300,000 left homeless of a total population of three million. About 500,000 have left the country and the destruction of property was estimated at more than six billion dollars. The homeless flooded into south Beirut and became squatters in shanty towns and abandoned buildings.

The fighting did not cease, however, even after the 30,000 strong and mostly Syrian APKF entered the country. For lack of authority, a vacuum arose in southern Lebanon, and here the tragedy continued. During the deployment of the APKF, Israel made it clear that they would not tolerate Syrian troops South of the so-called "Red Line" just below Sidon. South of this line they could use artillery against Israeli territory and a major confrontation might have taken place between Israeli and Syrian troops with unforeseen consequences.

Further to the South, Palestinian and Lebanese Leftist groups could operate free of any control. From their main bases in Nabatiyah, Tyre, Naqoura, Bint Jubayl and El Khiam they attacked Israel and the Christian Phalangists who were driven into an enclave where they continued to be supported with weapons and supplies by Israel.

The largest community in Lebanon is not comprised of the Maronite denominations, Christians, the Palestinians, or the Sunni Moslems who dominate the Arab world, but the Shiites, the minority branch of Islam who are the majority in Iran. The Shiites are mostly farmers and labourers and have traditionally lived in the south, the poorest region of the country, which borders Israel.

Although the Shiites have supported the Palestinians, their main grievance against them was the fact that the PLO had used their native area for mounting raids into Israel. The PLO's presence in southern Lebanon had in turn provided the Israelis with reason to attack the area either directly or through their ally, the Christian militia leader of the de facto Forces, Maj Saad Haddad, who controls a strip of territory on the border.

As the situation developed in early 1978 with frequent military raids on border settlements and retaliatory actions, it was expected that Israel would intervene in southern Lebanon at the first opportunity.

That opportunity came on 11 Mar 78 when landed Palestinian commando groups attacked civilian vehicular traffic on the Tel Aviv - Haifa coastal road. These attacks resulted in 37 Israelis killed and about 80 wounded.

Israeli Offensive - Mar 78

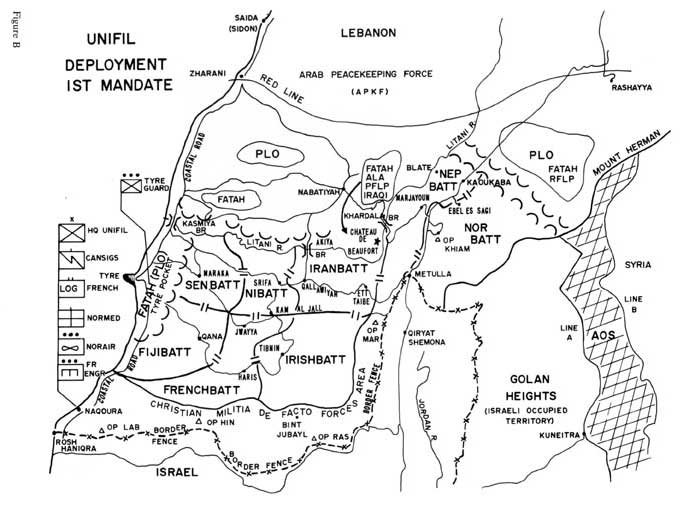

In quick retaliation for the PLO 11 Mar 78 suicidal raid, Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) started massing along the mountainous border with Lebanon, a jagged 100 km line that runs from the Mediterranean to the foothills of Mt Hermon (see map). After a 24-hour delay caused by rain and heavy clouds, the biggest antiterrorist raid ever mounted by Israel began. Starting with a night attack on 14-15 Mar 78 with infantry and armour supported by artillery, air and naval bombardments, the approximately 8,000 strong IDF force quickly carved out a 10 km deep 'security belt" the length of the border.

The IDF entered Lebanon at four points, and eventually linked up at the Litani River. One column pushed across the border from the coastal town of Rosh Haniqra to the Naqoura terrorist camp from which guerrillas in the past had launched Soviet made Katyusha rockets at Israeli settlements. At dawn, IDF aircraft bombed the port of Tyre and destroyed several ships reportedly carrying guerrilla arms. Missile boat and gunboat attacks along the coastal road between Tyre and Beirut interdicted Palestinian supply columns.

A second IDF advance struck at Bint Jubayl, a main PLO stronghold and continued northward. The third Israeli assault, from the country's northernmost sector, between Qiryat Shemona and Metulla, crossed the border and split in two. One portion pushed west to take the terrorist stronghold at En Taibe after close hand-to-hand combat. The other drove due North to Marjayoun and came under subsequent shelling by guerrilla units outside the towns of Ebel Es Saqi and Khiam. IDF aircraft knocked out the PLO artillery positions and Marjayoun's Christian population welcomed the IDF.

As a safety measure, a fourth IDF column drove across the eastern border to Khiam and then to the northeast on a guerrilla supply route. In the meantime, commandos attacked the southern Lebanese coastline. Missile boats strafed the port of Tyre and aircraft bombed PLO camps South of Beirut, where the terrorists who raided Israel on 11 Mar had been based. Frogmen landed at several points along the coast and attacked Palestinian command posts. The main IDF ground forces stopped short of crossing the Litani River or entering the Tyre pocket. North of the Red Line the APKF remained in control.

Central to the IDF plan was the decision to hold Israeli casualties to a minimum by moving slowly and making heavy use of artillery and armour as well as air strikes. The Israeli tactics seemed to have been successful in holding down their own casualties. By the third day of the invasion, the death toll stood at about 1,000 Palestinian and Lebanese civilians killed along with 19 Israeli soldiers and about 250 PLO commandos. The impact on the civilian population was devastating as an exodus of approximately 280,000 Lebanese and Palestinian refugees fled their homes and travelled North towards Sidon and Beirut. Of some 100 villages in Southern Lebanon, 10 were totally destroyed by the IDF and about 25 were subjected to extreme shelling.

UNIFIL Mandate

In the aftermath, Israel declared that the IDF would remain in southern Lebanon until they had a firm guarantee that Palestinians would never be allowed to return to this region. On 17 Mar 78 the representative of Lebanon spoke before the United Nations Security Council and demanded an immediate Israeli withdrawal.

This set the stage for an emergency session of the UN Security Council and on 19 Mar 78 the Council decided to dispatch a UN Peacekeeping Force to this area and adopted Resolution 425, which established the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL). Its mandate:

- to insert UN Peacekeeping Forces between the IDF and the PLO guerrillas to confirm that military action against Lebanese territorial integrity had ceased;

- to confirm the withdrawal of the IDF;

- to restore international peace and security in the Area of Operations (AO) and to ensure it was not used for hostile acts of any kind; and

- to assist the government of Lebanon in restoring its authority and sovereignty in the area south of the Litani River where pro-Israeli Christian villagers have long been at odds with Palestinians in neighbouring camps.

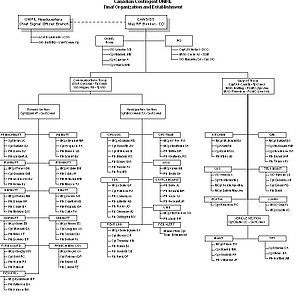

To enable UNIFIL to fulfil its responsibilities, it was initially estimated that it must deploy at least five battalions each of about 600 all ranks, in addition to logistics units, for a total strength in the order of 4,000. MGen Emmanual Alexander Erskine of Ghana, Chief of Staff of the United nations Truce Supervisory Organization in the Middle East (UNTSO), was appointed Commander of the Force in Lebanon.

Based on an urgent appeal from the UN Secretary General during the second week of Apr 78, Canada agreed to provide a signal unit to UNlFIL for an interim period not to extend beyond 1 Oct 78.

UNIFIL Deployment

UNTSO observers already stationed in Observation Posts (OPs) along the 1948 Armistice Line between Israel and Lebanon began forming the nucleus of a UNIFIL Tactical HQ at Naqoura on 20 Mar 78. Within 72 hours of the passage of Resolution 425, advance units of the Force began moving into southern Lebanon on 22 Mar 78.

The first contingent to arrive was an Iranian Company, which was detached from the Iranian Battalion serving with UNDOF (United nations Disengagement Observer Force) in the area of separation between Israel and Syria. Its initial task was to occupy the Akiya Bridge as well as the approaching terrain. This central sector gradually expanded and this company remained detached from UNDOF until replaced by a battalion from Iran in early Jun.

Almost at the same time, a French contingent arrived in Beirut and travelled south, establishing its HQ at a Lebanese barracks near Tyre. Their specific tasks included recce, security, and maintaining a presence in the vicinity of Kasmiya Bridge site as well as being prepared to form a Force Mobile Reserve for immediate deployment.

One day later a Swedish company and a 73 Canadian Signal Squadron detachment temporarily assigned from UNEF (United Nations Emergency Force) arrived in the AO. The Swedish contingent was ordered to occupy the Khardala Bridge and to ensure that all known and suspected fording sites into the AO were covered by observation. The Signals Detachment established initial Force radio communications by deploying personnel to each arriving contingent as well as a proposed logistic base at Zahrani and the Tactical HQ at Naqoura.

Soon after the UN Security Council vote, Norway, Nepal, Nigeria and Senegal in addition to France, Irat1 and Sweden had offered troop assistance.

The Norwegian battalion arrived in early Apr and was given responsibility for the Eastern sector and established its HQ at Ebel Es Saqi. The Swedish Company was relieved and redeployed in the Central Western sector with its HQ in Srifa.

The Nepalese contingent deployed into the AC during 13-16 Apr and was assigned the central eastern sector between Iranian and Norwegian battalions The recce party of the Canadian contingent departed Canada on 18 Apr and by 28 Apr the complete contingent arrived in the AO. The UNEF Signals detachment was relieved, a base camp was established at Naqoura and communications facilities rapidly expanded to meet the demands of a steadily increasing Force. The Senegalese contingent arrived over the period 28 Apr - 1 May 78 and deployed along the Tyre pocket in the northern half of the Western sector.

By 1 May 78 about 3,500 UN soldiers were deployed in the AO. However, the tensions in the area remained high as various factions of Palestinians, Lebanese Leftists and Rightists, Syrians, Iraqis and IDF mixed uneasily. Late on 2 May 78 a serious clash erupted between PLO guerrillas and FRENCHBATT in the Tyre area.

Alarmed by this rising disorder in which several UN troops were killed and injured, the UN Security Council voted to increase the size of UNIFIL from 4,000 to 6,000 troops. Shortly after this appeal for additional troops, Ireland and the Fiji Islands committed troops.

Deployment of a French Logistics battalion (FRENCHLOG) first to Zahrani, then to Naqoura, a French Engineer Company (FRENCHENGCOY) to Jwayya, a Norwegian Medical Company (NORMED) and a Norwegian Helicopter Flight (NORAIR) to Naqoura and a Norwegian Maintenance Company (NORMAINTCOY) to Tibnine all took place between 18 Apr and 2 May 78.

The Nigerian battalion arrived in mid-May and deployed into the Central Western Sector and the Swedish company temporarily assigned from UNEF returned to the Sinai on 17 May 78. By early Jun the main bodies of the Fijian, Irish and Iranian contingents arrived in the mission area. The Iranian Company temporarily detached from UNDOF was relieved and returned to the Golan Heights by mid-Jun 78.

IDF Withdrawal

The withdrawal of the IDF from occupied southern Lebanon eventually took place in four stages. The first occurred in the Marjayoun area on 11 Apr 78. This withdrawal included the Khardala Bridge and the villages of Kaoukaba and Ebel El Saqi, but did not include the villages of Marjayoun and El Khiam. The second withdrawal stage took place on 14 Apr 78 and included an area from a point on the Litani River two km west of Akiya Bridge to a depth of approximately five-six km including the main road through En Taibe.

In the third withdrawal on 30 Apr 78 the IDF moved to the 10 km deep security belt they seized on their initial advance across the border on 14-15 Mar 78. As in the case with previous stages, the process was verified by UNIFIL Observers.

On 13 Jun 78, the IDF withdrew from the remaining occupied territory. Unfortunately this last phase of the IDF withdrawal posed a major problem for UNIFIL. Instead of handing over evacuated areas to UNIFIL as had been done previously, the IDF turned over most of the evacuated area to the Christian de facto Forces in the area. The territory involved ran for the most part along the 1948 agreed Israel-Lebanon Armistice demarcation line. This area encompassed Sunni and Shiah Moslem villages as well as Christian enclaves.

UNIFIL Concept of Operations/Major Incidents

Throughout the buildup of the Force and the subsequent withdrawal stages of the IDF, UNIFIL redeployed its troops so that it could effectively extend its efforts to all the evacuated areas. Initially, UNIFIL deployed its available troops into a narrow zone between the Litani River and the forward positions reached by the IDF. A physical presence in the vicinity of or on the three bridge sites at Kasmiya, Akiya and Khardala was established. This deployment would continue until the withdrawal of the IDF from Lebanon and until the Lebanese government could extend its authority into the area of operations.

With the final withdrawal on 13 Jun 78, other boundary adjustments were made. Frenchbatt was redeployed in the south-western sector of the AO with its HQ at Haris. Fijibatt redeployed in the southern half of the western sector with its HQ at Qana. Adjustments were also made to the Nepbatt and Norbatt sectors. Irishbatt deployed into the south-eastern sector of the area of operations.

UNTSO military observers continued to man three of the five OPs along the border. Selected observers served in staff positions at UNIFIL HQ while others performed liaison duties as part of a special projects team. Two observers designated as Team MIKE were collocated with the IDF at Metulla and Team CHARLIE was the Call Sign assigned to two observers positioned at Chateau de Beaufort castle north of the Litani River to ensure liaison with the Palestinian command in that area. Team TANGO provided liaison to the newly formed Tyre Guard (after Frenchbatt's deployment), a composite UN Force of about 80 all ranks drawn from battalions on a two-week rotational duty basis.

Throughout its first mandate, UNIFIL activity was designed to ensure that a peaceful situation existed in the area of operations UNIFIL troops observed and supervised the cease-fire and controlled the movement of personnel and material into the area of operations. This control was exercised mainly by manning checkpoints at various points of entry as well as establishing observation posts and conducting patrols.

Frequent exchanges of fire (RPG, MG, mortar and artillery) between UNIFIL troops, Palestinians and Christians took place during the early states of UNIFIL. Although future exchanges generally became more isolated, firing between Chateau de Beaufort and the villages in the Marjayoun area were almost a daily occurrence and sometimes Nepbatt and Norbatt were subjected to indirect and occasional direct fire from these areas. Whenever fighting broke out in the area of Beirut, related factions in Southern Lebanon responded with similar clashes.

Major confrontations took place on 2-3 May 78 in Tyre barracks and later in mid-May 78 between 60 armed PLO who infiltrated Senbatt area and UN troops dispatched to the area as a composite reserve. Tension and the number of incidents usually increased during the periods of IDF staged withdrawals.

On 12 Jul 78, PLO elements captured 52 UN troops when the Tyre pocket was sealed by PLO elements. Although several troops were wounded their release was gained within a few hours of capture. During this incident an MRT (Mobile Repair Team)/Re-Supply Detail of three Canadians was captured by a group of approximately 40 PLO in the Tyre pocket. They were held for approximately three hours and then released unharmed. This was the only serious incident between Canadians and any of the factions in southern Lebanon.

In late Jul and early Aug 78 the Lebanese government attempted to assert its authority in the south by sending a 700-man Lebanese Army battalion into the area of operations via the Bekka Valley. Its advance was halted by the Christian militia de facto Forces on 2 Aug 78 as both the Lebanese Army and UN troops in the area came under heavy fire. The Lebanese government accused Israel of participating in this action. Intermittent shelling in the Kaoukaba, Marjayoun and Beaufort areas continued for two weeks as negotiations continually broke down. Unable to extend Lebanese authority in the South, this regular Lebanese Army unit was withdrawn. During the remainder of Aug and Sep 78 the pattern continued as heavily armed roadblocks in the Christian enclave impeded UNIFIL operations.

The relationship between the IDF and the de facto forces of Maj Haddad, who in essence provides Israel with a buffer zone, is the major factor that has prevented the complete restoration of Lebanese sovereignty in southern Lebanon. During the first six months of operation 11 members of UNIFIL had been killed and 52 injured as a result of firing incidents and mine explosions. On 18 Sep 78 the UNIFIL mandate was extended for an additional four months.

UNIFIL Deficiencies and Shortcomings

The initial establishment of UNIFIL did not provide for a HQ Company, which should have included Defence and Employment, Military Police, Transport, Engineers and Welfare Sections. These were provided by tasking already over-tasked contingents for personnel and support.

Rapid integration of multi-national HQ staff with the attendant language and procedural differences during the first six weeks resulted in misdirected staff work, confusing instructions and lack of direction in handling of incidents. Order came gradually and human endeavour overcame organizational weaknesses.

UN New York directed that contingents arrive self-sufficient and capable of supporting themselves administratively, logistically and operationally for at least six months. Some contingents such as the Nepalese and Fijian arrived lacking basic internal communications equipment. Due to previous contacts the CSO (Chief Signal Officer) had with Tadiran (Israel

Electronics Industries) and armed with verbal authority to undertake reasonable “short cuts”, direct purchases of urgently required communication equipment were effected. Fortunately, most equipment required such as telephones, field cable (WD-1 and quad), switchboards (SB-22), VHF Radio sets (AN/PRC- 77 and AN/VRC-46) and HF Radio sets (AN/GRC-I06) were available either off the shelf or within two weeks of order. In addition, arrangements were made with Tadiran to supply the Force with up to 10,000 batteries of all types each month.

Although Normaintcoy was to provide second and third line vehicle and telecommunications maintenance support, it had only one radio technician on strength and no test/repair facilities. During the first mandate, maintenance support had to be co-ordinated and provided by sharing personnel and equipment of those contingents with organic maintenance organizations. Second line maintenance of Canadian vehicles and generators could not be performed since they lacked spare parts. This placed an additional burden on the small CANSIGS maintenance section.

A serious lack of local electrical power and sanitation facilities existed in the area of Naqoura where in addition to HQ elements, CANSIGS, Normedcoy, Norair and Frenchlog were located. Consequently, living conditions were similar to those encountered in the field as opposed to a static or base location.

For future operations of this type these are "lessons learned". Overall, the system will work. The challenge is in making it work.

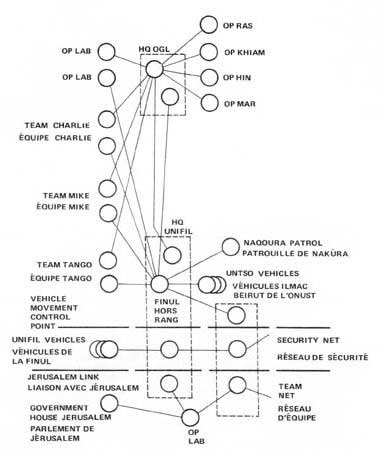

UNIFIL Communications

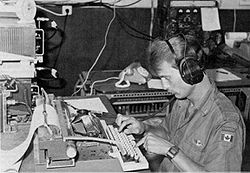

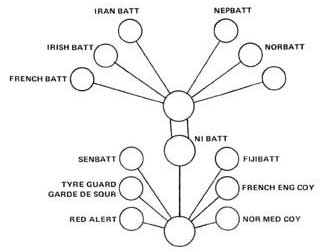

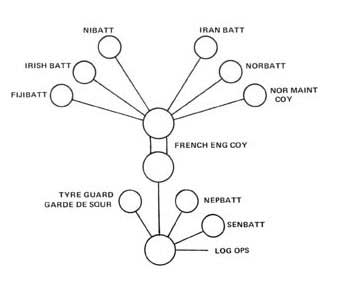

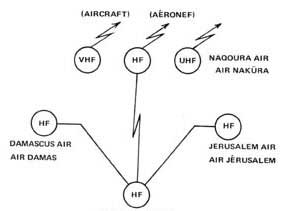

The Signals Branch at HQ UNIFIL was headed by the Chief Signal Officer (CSO) who was responsible for developing the Force signal plan and co-ordinating the implementation of force-wide communications between HQ UNIFIL, the deployed contingents and units, as well as HQ facilities. The CSO worked closely with contingent and unit signal officers and held regular Signal conferences to co-ordinate all aspects of communications.

A basic Signal Operating Instruction (SOl) was prepared in late Apr 78 to detail all aspects of Force communications. This SOl was subsequently updated with a series of Standing Signal Instructions (SSls). Although initially established for a staff of four the Signal Branch consisted of the CSO and his "jack of all trades" and expert Chief Comm Op, MWO George Burtoft, throughout the first mandate.

The principal tasks of the Signals Branch included:

- responsibility to the Force Commander (FC) for the efficient operation of all command and control communications;

- ensuring that proper interface existed between the three levels of communications within UNIFIL, namely -

- Unit-Level Communications. Internal communications (radio, line, Despatch Rider (DR) organized and operated by the contingent and normally using the standard equipment of its national armed forces;

- Force-Level Communications. Provided by CAN- SIGS during the first mandate. The unit operated from HQ UNIFIL with detachments providing rear link installations at each subordinate head- quarters; and

- UN Rear Link Communications. This link is provided and operated by UN civilians of the field operations service. It consists of a worldwide communication network that provides UNIFIL with a teletypewriter link via radio and landline or satellite to UN Head- quarters, New York, as well as other UN mission areas; and

- preparation of SSls on a variety of subjects to standardize contingent's communication procedures;

- preparation of plans and instructions for special operations, such as Red Alert and Force Reserve requirements;

- allocation and control of radio frequency assignments for Force-level and unit communications;

- liaison with Lebanese and Israeli military and civilian staffs on communications matters;

- local procurement action for communications and related equipments urgently required by contingents, units and HQ UNIFIL;

- preparation of budget forecasts; and

- advice to the Chief Administration Officer (CAO) on matters affecting procurement and interface of UN rear link communications.

The CANSIGS Story

The Beginning

"The world knows it can count on us and most importantly that it can count on Canadian communicators to provide the critical network which will be the nerve centre of the force which has been given an extremely difficult part to play in the Middle East." So said LGen RM Withers, VCDS (now Gen Withers, CDS), as he reviewed Canadian Signal Unit United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon at Kingston, Ontario on 23 April 1978 as the Unit began deployment to Lebanon.

Eleven days prior to this event, LCol Don Banks, CO 1st Canadian Signal Regiment had received the Warning Order from Commander FMC to provide the Canadian Contingent to UNIFIL.

Operation ANGORA was born. The Operation Order that followed on 14 Apr 78 was simple - the Regiment was tasked "…to form and mount a Signal Unit for UNIFIL to arrive in Tel Aviv, Israel by 1200 hrs 23 April." Almost a routine task for a Regiment that had only five years earlier deployed to Cairo, Egypt as the Canadian Contingent to UNEF 2 - Operation DANACA. The new unit was formed with a strength of 89 all ranks: 77 members from 1st Canadian Signal Regiment and 12 members from the Special Service Force. Equipment and supplies were gathered and prepared. Men were prepared. White paint, needles, rations, documentation, orders, range qualifications, spare parts, medical checks, hammers and nails, dental checks, time with families, conferences, and the list goes on, but all as part of a plan. The "system" worked: NDHQ, Mobile Command, Air Command, Air Transport Group, 437 Squadron, CFB Kingston, CCUNME, 73 Canadian Signal Squadron and Canadian Forces Supply System. But especially people worked. They are too numerous to mention here. Each person involved made an important contribution. On 20 April as the unit boarded 437 Squadron's 707 and Hercules aircraft at Trenton they did so with the knowledge that the "system" in the form of numerous individuals had and would continue to work for them. What follows is the story of the officers and men who were Canadian Signal Unit UNIFIL (or CANSIGS as the Unit's name was to be abbreviated in UNIFIL).

Deployment

CANSIGS deployed to the UNIFIL Area of operations during the period 18-28 Apr 78. The Advance Party deployed via Trenton, Lahr, Cairo and Tel Aviv on 18 April. Liaison was established with the Commander and staff CCUNME, UNIFIL and 73 Canadian Signal Troop in Lebanon. A ground recce was completed by 22 April. Recce reports were sent back to assist the Main Body in preparing for deployment. The Main Body deployed by air from Trenton to Tel Aviv via Lahr. Airlift was provided by one 707 flight on 23 April and ten Hercules flights during the period 23-27 April. The Main Body staged through an Israeli Defence Force camp, 421 IDF Camp, just outside Tel Aviv. This staging camp, operated by CCUNME, was established to conduct all administrative processing and to allow the unit to marry-up with its equipment before deploying into Lebanon. The Main Body, fully briefed on the operation and with all of its equipment, cleared the staging camp and deployed into Lebanon by 28 April.

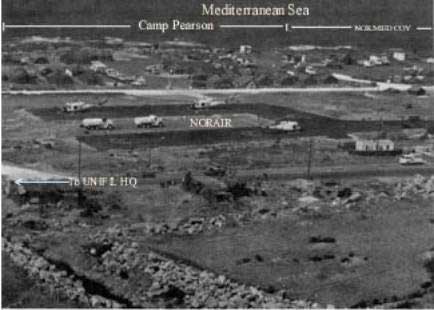

The deployment into the UNIFIL Area of Operations went smoothly. 73 Canadian Signal Detachment in Lebanon under command of Capt Blaine Williams handed over their established radio detachments on 28 April and returned to Ismailia. CANSIGS established a HQ and base camp, later to be named Camp Pearson, near UNIFIL HQ in Naqoura, and deployed radio detachments throughout the AO.

The Task

CANSIGS was tasked to provide force-level communications for UNIFIL, excluding internal unit communications and UNIFIL rear link communications. The Unit was also tasked to provide Canadian Contingent rear link communications to Canada via Ismailia.

Tasks could, and did, change daily especially during the first weeks of the operation. UNIFIL was initially established as a force of 4,000. This number grew to 6,000 by the 1st of June but with no immediate increase in the strength of CANSIGS. Consequently, Unit tasks were juggled and refined in response to the operational requirements. The following list of Unit tasks showing effective dates demonstrates that what the Unit did was not entirely what had been planned for it to do.

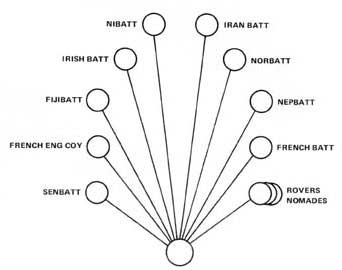

- UNIFIL Communications - Voice Command/ Force Message Net, Logistics Net and Air Ground Net (Figures 1 to 3):

- UNIFIL HQ (Control Stations) (Naqoura) 28 Apr

- FRENCHBATT (Haris) 28 Apr

- Forward Logistics Base (Zahrani) 28 Apr - 14 May

- NEPBATT (Blate) 28 Apr

- SWEDCOY (Replaced by NIBATT) (Srifa) 28 Apr - 13 May

- IRANCOY (Subsequently lRANBATT) (Quallawiyah) 28 Apr

- SENBATT (Marake) 28 Apr

- NORBATT (Ebel Es Saqi) 29 Apr

- NORAIR- (Naqoura) 10 May

- NIBATT (Kam Al Jall) 13 May

- *IRISHBATT (Tibnin) 13 May

- *Force Reserve (Red Alert) (Naqoura) 25 May

- *FIJIBATT (Qana) 6 Jun

- *Tyre Guard (Tyre) 20 Jun

- *FRENCHENGCOY (Jwayya) 8 Jul

- *Lebanese Army (Kaoukaba) 1-4 Aug

- UNIFIL HQ Telephone Switchboard Service (Naqoura) 29 Apr

- Signals Despatch/ Air Despatch Service Naqoura) 29 Apr

- *Operations/Force Team Net (Figures 4 & 5) (Naqoura) 29 Apr

- Canadian Rear Link (Naqoura) (Figure 6) 29 Apr

- *Local Defence and Perimeter Security (Naqoura) 28 Apr

- Maintenance -First and Second Line for communication equipment. First and some Second Line for vehicles and generators (Naqoura) 28 Apr

- *Feeding UNIFIL HQ Staff (all ranks) (Naqoura) 1 Jun - 18 Jul

* Tasks not included in the original plan.

So it was. The original plan served to get the Unit on the ground (to the Start Line). From then on there was a job to do -get on with it! Vehicles and equipment were "borrowed" compliments of the Chief Signal Officer, LCol Lackonick, and his Chief Comm Op, WO Burtoft. Detachments were reduced in numbers to man the extra equipment. It was not a matter of "can do". It was simply a matter of satisfying the operational requirements of the Force Commander to the best of the Unit's abilities and capabilities.

But the Unit was seriously undermanned. There were only two cooks on establishment. There were two vehicle technicians to maintain vehicles, some of which had been sent to the Middle East from Canada in 1973. Numbers, of course, do not tell the complete story. Two cooks, for example, may appear to be an adequate number for a small unit. However, consider the job they had to perform. MCpl MacDonald and Cpl (later MCpl) Wallet were required to feed the fifty-odd personnel normally stationed at Camp Pearson. On 1 June this number doubled when the Unit was required to feed up to 50 personnel from UNIFIL HQ. But preparing meals was only part of their task. There was no approved ration scale for UNIFIL - this was produced. There was no ration supply system until 10 July - trips were made daily to the local supermarket in Nahariya, Israel where shopping carts were filled with the Unit's needs. Rations had to be of the type and quantity that could be apportioned between the deployed detachments and the main kitchen. All had to be accounted for. Notwithstanding the problems, the Unit was fed, and fed well. As a reward the cooks were given Sunday mornings off. Sunday brunch was an individual responsibility - cook it yourself.

Camp Pearson

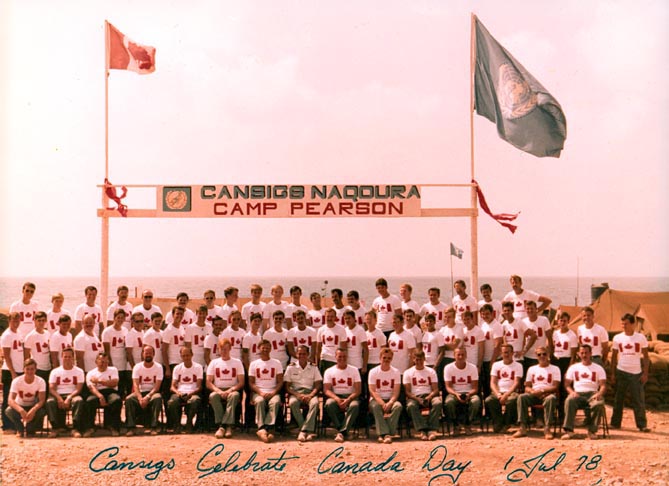

Camp Pearson, as mentioned previously, was established near UNIFIL HQ in Naqoura. The camp was named after the late Lester B Pearson, a Canadian name familiar to all members of the United Nations. Appropriately, the ceremony of erecting a camp gate and signpost coincided with the celebration of Canada Day on 1 July 1978.

Camp Pearson provided tented accommodation and working areas for Unit HQ, Support Troop and the communications detachments working at UNIFIL HQ. Living in Camp Pearson was a luxury! The camp was set on a bulldozed flatland extending to the shore of the Mediterranean. Rocks! They grew everywhere! Protective bunkers, latrines, ablution facilities, etc, were for the most part dug in by hand. Washed gravel sufficed as flooring material in the tents. Other improvements were made as manpower, time and money permitted. Concrete floors were installed in the Mess Hall (Mac Al’s), canteen (Macabbe Inn) and vehicle maintenance area (Orv's Place). Old railway tracks "borrowed" from a nearby abandoned railway served as forms for the concrete floors. Manhandling these in 35 degree C heat also served as good physical conditioning. Imagine the following: "Sergeant Major Currie!" "Yes Sir". "Do you remember those 45 cubic metres of ready-mix concrete we've been trying to get in from Israel for the last month?" "Yes Sir". "Well, it's arriving at 0900 hrs - all of it!" Panic? Hardly! Let a contract? Hardly! Get on with it! Get the TQ3 Rad Op, the Cook, the Trooper and everyone else available and get the job done.

From April until June Camp Pearson was built. Most of the work was done in the evenings. Seven days a week, (later reduced to six) the daily routine was: work from 0700 to 1300 hrs, lunch and rest during the afternoon heat (if the time could be spared) and then return to work after supper for two or three hours of hard physical labour. Then, for those still wanting excitement, the canteen was opened and a movie shown. By mid-June, the camp was "comfortable" and the evening work schedule replaced by a popular programme of volleyball, both inter-section and inter-contingent. CANSIGS personnel never could determine why, since they had to teach the Fijians how to play volleyball, the Fijians won all the games!

Camp Pearson, although the hub of CANSIGS' activities, existed primarily to support the deployed detachments. These detachments were "Priority One" for food, movies, CANEX items and work effort. Support personnel located at Camp Pearson were obliged to visit the deployed detachments at least once every two weeks. Seeing is believing! Thus, the SDS (Signals Despatch Service), Re-Supply and MRT were never wanting for someone to ride "shotgun".

Camp Pearson, although the hub of CANSIGS' activities, existed primarily to support the deployed detachments. These detachments were "Priority One" for food, movies, CANEX items and work effort. Support personnel located at Camp Pearson were obliged to visit the deployed detachments at least once every two weeks. Seeing is believing! Thus, the SDS (Signals Despatch Service), Re-Supply and MRT were never wanting for someone to ride "shotgun".

The Deployed Detachments

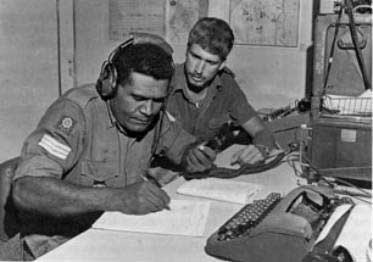

Four-man radio detachments were deployed with each of the national contingents throughout the Area of Operations.

Life at a detachment was much the same as at Camp Pearson but it was more spartan. Detachments, for the most part, cooked their own meals from the fresh rations and water delivered twice weekly, or on demand, from Camp Pearson. Cook stoves were of the two-burner, camp stove variety, which seriously limited the choice of meals. Barbecues and the odd propane stove appeared as ingenuity responded to the rumblings of stomachs.

In all cases, CANSIGS' radio detachments were made to feel at home with the various contingents. Master Corporal detachment commanders negotiated with Contingent Commanders for living and working accommodations. If it didn't exist, it was built. To the credit of the Contingent Commanders, CANSIGS personnel received more than fair treatment when contingent accommodation was allocated.

Assignment to a radio detachment meant more than sending and receiving messages. CANSIGS personnel were a vital part of the operation. Canadians are experienced in UN operations and more is expected of them. In many cases, detachment radio operators formed a vital part of the contingent's operations staff. Bilingual operators at the French speaking contingents translated messages to English, the official working language of UNIFIL. Without exception, the detachments were highly regarded by the contingents with which they worked.

Signals Despatch Service (SDS) was provided daily throughout the area of operation. Two vehicles, normally 1/4-ton jeeps, left Camp Pearson at 0700 hrs each day to visit all battalion locations. The area of operation was divided roughly into two sectors, East and West. One vehicle covered each sector and returned to Camp Pearson late in the afternoon. Each afternoon, a Despatch Rider boarded a NORAIR helicopter and made the second Despatch Service run of the day to all deployed battalions with about a one minute stop at each location. Special Despatch Rider service (SDR) was provided when required.

SDS was not any easy task. It was not a simple matter of touring Southern Lebanon each day. Roads were torturous and the heat of the summer made the trip even more uncomfortable. Frequently, the roads were closed by the protagonists in the areas with a resultant disruption of service. Old vehicles broke down or fell apart but the mail went through. Notwithstanding poor road conditions, unreliable vehicles and an average 2500 km per week, there were few accidents. CANSIGS had a good vehicle safety record. During six months of driving over 165,000 difficult kilometres, five accidents were suffered of which only two were serious.

The Private Performs - An Assessment by the Chief Comm Op

The personnel who deployed with CANSIGS in UNIFIL were a representative cross-section of servicemen then available for an operational tasking of this nature. Accordingly, UNIFIL provided an excellent opportunity to measure the quality of performance of the present day young serviceman in an operational theatre. As experience, or lack thereof, could be an important factor in such a situation it is noteworthy to comment on the performance of a large number of TQ3 Rad Op privates who suddenly found themselves in a war zone setting.

Operation ANGORA was not the first UN Peace-keeping tour of duty for most of the four officers and 13 WOs and Senior NCOs assigned to UNIFIL. For some Senior NCOs and all the privates, however, it was the first exposure to a hostile environment of frequent exchanges of gunfire, minefields and a high density of unexploded cluster bombs. Wearing helmets and flak jackets and carrying personal weapons as well as keeping a layer of sand bags on vehicle floors soon became standard protection against the constant threat to life and limb.

For the 40 or so inexperienced TQ3 Rad Ops a natural feeling of bewilderment and apprehension was evident during the hectic preparation phase in Canada and to a greater degree during transit to the Middle East. These concerns were natural and were anticipated by the officers and Senior NCOs.

Once on the ground in Lebanon, the TQ3 private made a quick appreciation. He knew that he was a young man having had basic military training, basic trades training, and, perhaps, language training. Now, he suddenly found himself working as a Rad Op under unusual circumstances. Gone was his social life, time off, leave, his mother, pay and, for all intents and purposes, his On-Job-Training (OJT) programs. He was now confronted with new priorities: danger, real radio traffic, survival, his job, his peers and lastly, his personal comfort. The real meaning of wearing a uniform as a member of a military force under difficult surroundings was now a stark reality. Fortunately, as officers and Senior NCOs made sound decisions, confidence levels rose and a keen sense of comradeship within CANSIGS developed. This led to immediate respect from other contributing nations in UNIFIL as well as the various fighting factions within the area.

In a very few isolated cases the TQ3 private tended to withdraw and thought that by sleeping as much as possible he could avoid the reality of the situation. Of course this couldn't last any longer than a few days and he soon realized that he had no alternative but to apply himself and learn as much as he could in as short a time as possible. It was basic leadership by his superiors that soon got him going. What he learned was not contained in any OJT program nor could it be taught by formal trades training. His first lesson was to develop a sense of urgency - without it, he was lost. This was soon followed by a sense of responsibility, a sense of purpose, imagination, self confidence, both in himself and in his job, and last but not least, courage. His leaders achieved this primarily through recognition of the individual, reassurance, showing by example and creating a competitive spirit between detachments. This quickly had the TQ3 out of his "shell" and performing magnificently.

Upon returning to Canada, what was once an average Rad Op TQ3 private, perhaps a little lazy and somewhat preoccupied, was now transformed into a proud professional. The secret was to motivate the man, as an individual, so he could develop and learn to take his place in a responsible position. Lebanon proved that there is essentially nothing wrong with the "calibre" of the present recruit when under fire and, that given the proper learning environment, motivation and re-assurance from his superiors, he is just as effective as his counterpart of yesteryear.

The onus was on the NCO. Trades training and OJT gave him the basic skills that represent about 30 per cent of his overall effectiveness in the field. Without the other 70 per cent provided through motivation of the individual by his superiors, those basic skills would be next to worthless.

The Lighter Side

Naturally, life in Lebanon was not all work. Parades, visits, entertainment, leave and sports added the variety essential for good morale. Visitors from near and far were a common and welcome sight around Camp Pearson. The Unit was always glad to see Commander CCUNME in the UNIFIL Area of Operations. BGen B Baile was on the ground to welcome the Unit on its arrival in Lebanon and returned to say farewell on 23 May. His replacement, BGen R Evraire, was a frequent and welcome visitor to Camp Pearson and the detachments. Mrs Evraire, accompanying the Commander for Canada Day celebrations and the Unit's Medals Parade on 15 September, brought warmth and sunshine even to the shores of the Mediterranean. Mr Couvrette, Canadian Ambassador to Lebanon, along with his Military Attaché LCol (now Col) R Duguid visited the Unit for its Medals Parade. With a reputation for warm hospitality and fine food, Camp Pearson was also a popular stopover for visiting dignitaries from other countries.

All of the Unit's personnel enjoyed leave in the Middle East and in Europe. Each detachment or section was allowed to have one person on leave at anyone time. For the deployed detachments this was often only a visit to Camp Pearson for one or two days to relax on the beach. Many took the opportunity to avail themselves of a hotel room in Nahariya or Tel Aviv. All members of the Unit who requested 2G leave were able to spend two weeks in Germany with their wives.

For those who were not away on leave, entertainment was provided in Lebanon. Movies made the rounds through each of the detachments, courtesy of the SDS. Live entertainment was provided by the CANLOGGERS from Ismailia on Canada Day and for the Medals Day activities. A "Gong Show", on one of these occasions, served to demonstrate the considerable talent available within the Unit itself! Light "sports" such as darts and card games became a standard activity following the popular Saturday evening barbecue at the Macabbe Inn. As was proved over and over again that life could be fun even when the job was tough and even when the sound of gunfire overwhelmed the noise of the generators.

Contingency Plan - Withdrawal of Canadian Signal Unit

The Canadian Contingent continually impressed on HQ UNIFIL the requirement to replace CANSIGS by 1 Oct 78. UNIFIL, however, took little action until late July at which time an action request was sent to UN New York. In early Aug, UN New York advised that no other country would agree to provide an English-speaking Signal Unit to replace CANSIGS.

Suggestions for an alternate plan were forwarded to New York in Aug. This plan was based primarily on requesting some of the contributing countries to provide regimental English-speaking signallers to man their rear links, (Norair, Normaint, Norbatt, Irbatt, Fijibatt, and Nibatt). HQ duty officers would man operation centres. Those countries which could not provide English-speaking radio operators for their rear links (Frenchbatt, FrenchEngrCoy, Senbatt, Iranbatt, and Nepbatt), would be assigned teams of newly-recruited UN civilian field service radio officers. The remaining functions of SDS, switchboard, line and telecommunications maintenance were to be handled by appropriate UN civilians.

Ireland agreed to provide a CSO to co-ordinate the operation of the resultant organization. Although recruitment of UN civilian radio officers was slow, and newly arrived radio officers had to undergo equipment and procedural familiarization training, most language barriers were overcome to a degree and all communications were handed over on 1 Oct 78.

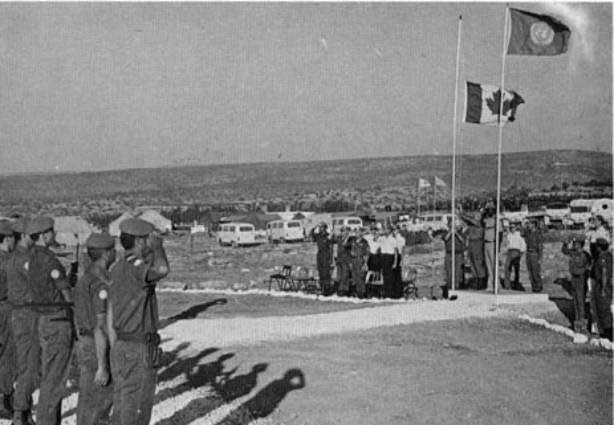

The Withdrawal

On 1 Oct 1978 CANSIGS handed over responsibility for UNIFIL communications to a mixed group of regimental signallers and UN civilians. In the preceding weeks, the Unit had been busy training the replacements and packing up for the trip home. On 1 Oct, the detachments returned to Camp Pearson for a farewell parade, a ceremonial lowering of the Canadian flag and an all-ranks dinner in the evening. The Force Commander UNIFIL, MGen Erskine, will probably never forget a rather emotional rendition of "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow" by 116 Canadians in a tent set on the rocks of Naqoura.

CANSIGS returned to Canada quite a different unit than the one that left six months previously. A proud record of achievement had been established in the tradition of other Signal Squadrons and Units that have served with the UN. Officers and men were matured by a unique experience together. While they all have gone their separate routes, it is doubtful if any will forget Canadian Signal Unit UNIFIL. They came to serve - they served well.

Conclusion

Unlike other peacekeeping operations in the Middle East, UNIFIL worked without precise agreement between opposing parties and in an area where for several years there had been little or no exercise of legitimate civil authority by the government in Lebanon. By the end of the first mandate the Force had established the necessary framework of command, staff and logistics in circumstances of great difficulty.

In spite of these enormous difficulties UNIFIL has been successful in fulfilling much of its mandate. The complete withdrawal of the IDF was carefully supervised and except for the border area, confirmed. The Force exerted control over most of the AO and where fully deployed progressive normalization of life took place. By the end of Sep 78 about 90 per cent of the Lebanese refugees had returned to the villages and towns from which they fled. Clearly the presence of UN Troops helped restore a measure of peace and tranquility in the South. However, much remained to be done. UNIFIL had yet to exert control over the entire area of operations and the process of assisting the Lebanese government to assert and restore its authority in the South had only begun. The task continues to this date. Whatever the final outcome, UNIFIL can be assured of the best wishes of the Canadians who proudly served under the UN flag in Southern Lebanon.

|

| The officers and men of Canadian Signal Unit UNIFIL (CANSIGS) celebrate Canada Day and the naming of their camp ‘Camp Pearson’ on 1 Jul 78. |

Notes

- ↑ Originally Published in Communications and Electronics Newsletter 1981/2