Cracking the Code

Contents

Canadian Army SIGINT in the Second World War

By Major Rob Martin

Royal Military College of Canada

Winter 2004

|

| |

| Cleve, Germany, 1945 | Grande Prairie, Alberta, 1942 |

- General Charles Foulkes

In December 1945 the newly appointed Chief of the General Staff, General Charles Foulkes, articulated his strong sentiments regarding the value of wireless intelligence in a confidential memorandum to the Canadian government entitled "A proposal for the Establishment of a National Intelligence Organization."[2] In essence this work, which contributed to the development of a framework for Canadian Intelligence in the early post-War environment, served as witness to the Canadian intelligence efforts - particularly 'wireless' - of the past six years. General Foulkes' testimony was certainly heartfelt; he had been on the receiving end of such 'wireless' intelligence as Commander of both the 2nd Canadian Division and the First Canadian Corps in North-West Europe immediately prior to and following the invasion of France in June 1944. But the memorandum does little to illuminate the efforts of the various Canadian 'Special Wireless' (S.W.) organizations to whom he covertly pays tribute, whose soldiers 'served in silence' in Canada and abroad between 1939-46.[3] Although an undetermined amount of information regarding 'S.W.' or 'Y' operations during the war remains outside of the public domain, there is enough material now available to provide substantial insight into the Canadian Army's SIGINT effort in the Second World War: this paper is an attempt to do so.

Background

The concept of gathering intelligence from wireless intercept was not new to the Canadian Army at the commencement of the Second World War, although it was not being effectively practiced at the time. During the later stages of the First World War, a small number of Canadian soldiers (German interpreters and telegraph operators) on the Western Front were being employed to "intercept and decode enemy Wireless messages" by mid-August 1917, "when [a] station consisting of a MK III Tuner and 3 valve Amplifier was erected in the Bois de Riaumont"[4] (the earliest record of Canadian Corps intercept of German communications - predominantly telephone (non-wireless) - occurred about 1 January 1917, at "No 6 Post", Neuville St. Vaast).[5] From August 1917 onward the Canadians, in support of a broader Allied wireless collection effort, conducted such intercept against German forces until at least 21 August 1918, when a hastily erected site at Demuin was closed.[6] By the conclusion of hostilities each Divisional Signal Company was responsible to provide services that included the interception of German military communications.[7] Intercept successes varied, from the early warning of German attack planning against Hill 70 provided on 15 March 1918 that led to German defeat, to what Royal Canadian Corps of Signals Lieutenant-Colonel W. Arthur Steel considered "perhaps the most useful contribution of these [intercept] stations. . . the assistance they gave in determining the units comprising the German forces on [the] front."[8] At demobilization, however, the fledgling wireless intercept elements suffered the same fate as many other Canadian Expeditionary Force (C.E.F.) wartime establishments - they were struck off strength - and no effort was made to create or sustain any organic Canadian Army capability in wireless intelligence, strategic or tactical, until the spring of 1938[9] (wireless intercept physically began in Canada in 1925, when the British Admiralty requested that the Canadian Navy "build [italics mine] a wireless and direction-finding station at Esquimalt. . . to work with a similar station at Singapore": the station was manned by Royal Navy seamen).[10] At the outbreak of the Second World War, Brigadier-General Macklin, later Adjutant-General of the Army, succinctly summed up Canada's abilities to conduct wireless intelligence operations in support of any war effort thusly: "Wireless Organization Radio Intelligence, Signal Security and cipher was really in hand in the War Office when the War began - we were nowhere".[11]

Canada

Germany's attack into Poland in early September 1939 served as a catalyst for the Canadian Army to consider and quickly implement wireless collection and analysis capabilities, at both the strategic and tactical levels. By October 1939, the nucleus of the Army's first static Special Wireless site was being formed in Ottawa at the Army Signals Station at Rockliffe Airport. As Bob Grant, a young 19-year old signaler who later commanded No 2 Canadian Special Wireless Section Type B in North-West Europe in 1944-45, recalled in the mid-1980s:

Bill, Ray, and I - were told to report to Major W.J. Megill at the Directorate of Signals offices in the Elgin Building. He informed us that Army Signals were going to start a new business known as "Y." He said: "at the moment we know nothing about it, but we'll give you a room, some radio equipment, and set you up in the basement of VER [the Army Signal Station] with RESTRICTED ENTRY. So go down there and start." [12] From this rather vague direction, the small "experimental unit" began almost immediately to intercept the "jumbled letters of enciphered messages." Since there was no cryptanalytic expertise (understanding the ability to convert an encrypted message into plain text without the knowledge of the encoding algorithm or 'key') in Canada at the time, Captain H.D.W. Wethey, the unit's first Officer Commanding, was quickly dispatched to Britain to determine what to do with the intercepted material.[13] His liaison visit was opportune for both countries. It was discovered that, due to signal propagation or 'radio skip', the Canadian station was picking up 'illicit' transmissions between German agents operating in the Western Hemisphere and their controllers in Berlin that were not being heard by British intercept sites. A cooperative working relationship between the two organizations quickly developed. Back in Canada, the Army arranged with the Royal Canadian Navy (R.C.N.) to have their "listening stations", located in the Maritimes, provide direction-finding 'lines of bearing' on Army target transmitters, since the Rockliffe unit had no such ability.[14] The size of the S.W. site at Rockliffe expanded rapidly, in terms of equipment, capability and personnel. By mid-1941, to address the need for additional space a permanent intercept site had been constructed south of the city at Leitrim, and No 1 Special Wireless Station Leitrim was formed.[15] Operationally by this time Canadian intercept operators, now under the command of Captain Ed Drake (a "serious young man with a flair for getting the most out of [his] subordinates"[16]), had amassed a substantial file on "German espionage in the western hemisphere"; among other tasks they were "following the activities of some fifty-two enemy agents", and "had managed to read 740 German messages."[17] As historian Wesley Wark notes, it was during this period that "Canada thus gained its first taste of the fruits of signals intelligence."[18]

|

| No. 1 S.W. Station, 1941 |

The growth of Army Special Wireless in Canada was complimented by higher level Government of Canada interest in the dividends of such work. Concurrent with the expansion of the Rockliffe site to Leitrim in 1941 was the creation, in a room of the National Research Council (N.R.C.) on Montreal Road in Ottawa, of a small cryptanalytic unit (the 'Examination Unit') under the direction of the Department of External Affairs.[19] In November 1940, Captain Drake had discussions in Washington, D.C., with the U.S. Army Chief Signal Officer (C.S.O.) General Maughborne, who recommended the immediate formation in Canada of an Army "Crypto-Analytic Bureau", with a long-term full-up establishment of approximately 200 personnel.[20] Maughborne considered that "such a unit could produce [information] of the highest value to a country at war." Captain Drake subsequently recommended to the Chiefs of Staff Committee the establishment of a jointly manned (for efficiency of personnel) Cryptographic Bureau, but in early December his proposal was flatly rejected; potential duplication of effort amongst the Allies and high cost were cited as the official explanations.[21] Undaunted by this rebuff, Drake and his R.C.N counterpart, Lieutenant C.H. Little, pursued the issue through their chains-of-command, and in relatively short order (spring 1941) the subject came to the attention of Dr. H.L. Keenleyside at External Affairs, who championed the cryptanalytic cause for the Government.

The Canadian Examination Unit, under the leadership of noted American cryptanalyst Herbert Osborne Yardley of The American Black Chamber infamy, commenced operations in June 1941 with a very small inter-departmental staff of nine (on loan to the unit were personnel from the N.R.C., the Army, Cable Censorship, the Post Office Department, and the RCMP).[22] Interestingly, in order not to raise the ire of U.S. or British SIGINT organizations of the day, Yardley worked in Canada under the name Herbert Osborne (he was reviled and still much maligned by the U.S. and Britain for disclosing SIGINT secrets in his 1931 book). Yardley's employment was ultimately terminated after six months, once both countries found out that he was working for the Canadian cryptanalytic cause and pressured Canada - on the overt threat of breaking rapidly expanding SIGINT relationships - for his removal. [23] Thus in mid-1941 began the close working relationship between the External Affairs-controlled Examination Unit and the Canadian Army. Aside from Army personnel who were seconded to the unit Army Special Wireless Stations and, later in the war, listening sites of the RCN and RCAF, provided intercepted traffic - initially German 'illicit', then Vichy French and Japanese - to the Examination Unit, who analyzed (e.g. decrypted, translated) the material and were thus able to feed "a continuous stream of intelligence to the Department of External Affairs and to the Directors of Intelligence."[24]

Army SIGINT collection efforts in Canada rapidly expanded with the entrance of Japan into the war. In the fall of 1941, even prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December, the Army had begun construction of a second 'Special Wireless Station' in Victoria, British Columbia, to enable wireless intercept of the Pacific region.[25] Prior to the conclusion of the war in August 1945, two additional Army Special Wireless Stations were - or had been - in operation, both sites also being located in the West. No. 2 Special Wireless Station was established in a former Forestry Station about a mile northeast of Grande Prairie, Alberta, on 8 May 1942, when one officer and 17 other ranks arrived there by rail.[26] Following over a month of construction and equipment installation, limited operations at the site commenced on 22 June, following the erection of "four 73' steel" antenna masts at the "corners of the property."[27] The fourth site, No 4 Special Wireless Station, was briefly established in the Chilkotin region of British Columbia at Riske Creek in the spring of 1944 at a lodge "built by a wealthy American", but was closed in July of that year perhaps due to manning difficulties.[28] The War Diaries of No's 1 and 2 Special Wireless Stations, while providing accurate daily descriptions of the local weather, and sporting and social activities of the units, shed little light on their operational mission, and rightly so. As an early entry into the diary of No. 2 Special Wireless Station admits, "[i]n the interests of Security, and owing to the extremely Secret nature of the work. . . no information which would divulge the actual character of the work performed" would be recorded.[29]

|

| |

| No. 2 S.W. Station, 1942 | No. 4 S.W. Station, 1944 |

Each of the Special Wireless Stations were administratively subordinate to the military districts wherein they resided, but were under the operational control of an Army 'Discrimination Unit' in Ottawa, commanded by the energetic Captain Ed Drake. The Discrimination Unit, which was initially co-located with the Examination Unit on Laurier Avenue, was responsible for traffic analysis - "a close study of the details of how the enemy's signal system operates"[30] - of the raw material from the intercept sites prior to its passage to the Examination Unit and/or British and American partner agencies (the British Radio Security Service or Government Code and Cipher School, and the U.S. Army's Signal Security Agency) for decryption. The unit, also known as MI2, was a cooperative Signal and Intelligence Corps organization authorized in the fall of 1940 that, at it's wartime peak, employed in excess of 100 personnel.[31]

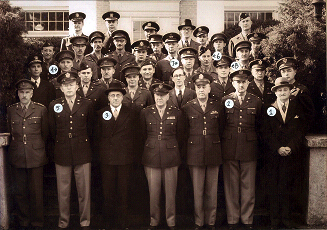

A seminal 'Radio Intelligence Conference,' convened in Washington, D.C. from April 6-16, 1942, began the formalization of geographic division of intercept efforts between Britain, Canada and the United States against the Axis powers.[32] The Canadian Army would continue to provide encrypted German 'illicit' traffic to the Examination Unit, who would then disseminate the decrypted plain-language intelligence products to Britain and the U.S.; it would also expand collection to include Japanese military, diplomatic and commercial traffic.[33] The conference laid the groundwork for future cooperation amongst the three partners, with substantial agreements made on "research into ionospheric effects, and the encrypting and decrypting of non-Morse transmissions": as author John Bryden comments, "[s]ystematic cooperation among the three countries on the exchange of wireless intelligence. . . dates from [this] conference."[34] A subsequent conference, held in Washington, D.C., in March 1944 ('[a] veritable Who's Who in Special Intelligence' - Captain Drake is #4 in the photo; William Friedman, considered the 'father' of American cryptanalysis, is #1), refined Allied Special Wireless division of effort further, and increased the visibility of the Canadian Discrimination Unit amongst the Allies by fully partnering it - albeit as 'junior' partner - with the U.S. Signal Security Agency: "From now to the end of the war, the [Discrimination Unit] work. . . in Ottawa became a kind of American branch-plant operation. Arlington set the tasks, distributed the raw material, and received the results."[35]

|

| Signals Conference, 1944 |

Special Wireless operations in Canada had grown from virtually nothing in 1939 to that of SIGINT junior partner status with the Allies by 1944. Contributing immensely to this success were hundreds of men and women employed within the Army Special Wireless system, be they Signal Corps operators or Intelligence Corps analysts and linguists. But theirs was not the only Army SIGINT contribution provided by Canada during the war - Canadian Army tactical Special Wireless units also played their part.

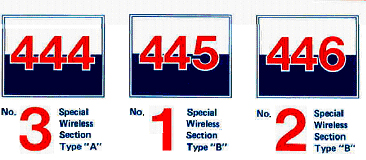

Europe

Canadian Army soldiers were not involved solely with static wireless intercept and analysis in Canada during the Second World War. As important as the static mission was to the broader strategic Allied cause, Canadian tactical 'special wireless' units provided a similarly important function to their operational commanders, be they British or Canadian. Almost parallel with the establishment and development of the initial Army Special Wireless Station in Ottawa was the mobilization of Special Wireless Sections for service in tactical operations. Discussions to form such Canadian units began at Canadian Military Headquarters (C.M.H.Q.) in London in May of 1940, and the first 'Special Wireless' field unit - "Special Wireless Section Type "B" R.C. Sigs. (A.F.)", under the command of Lieutenant J.W. Anderson[36] - was established in Ottawa on 5 December 1940.[37] Organized "SOLELY FOR INTELLIGENCE DUTIES and NOT for monitoring our own wireless traffic"[38], Canada fielded a total of five Army Special Wireless units (one Type 'A'; two Type 'B'; one short-lived Type 'C'; and one Special Wireless Group) that saw service in Italy, Northwest Europe, and the Pacific Theatre through 1945.

Understandably each of the wireless elements had similar structures, with a Special Wireless Section (Intercept, Directing Finding, and Service Support components) and a Wireless Intelligence Section (Linguists, Analysts) combining to form the unit. Overall command was vested in a Royal Canadian Corps of Signals officer, who was responsible for administration, discipline, communication support, and unit movement. The Officer Commanding the Wireless Intelligence Section "controlled and assigned the frequency coverage of the various radios in the set vans and the Direction Finding (DF) tasks.[39] This chain-of-command anomaly did create some tension during the formative period of the units - actually up until mid-1943 - as Elliot notes in Scarlet to Green:

The [Intelligence] men complained that their Signals unit C.O. lacked interest and understanding of their role, that they got no trades pay, and that their general administration was poor. Their dissatisfaction stemmed in large part from the broader question of who actually "owned" the Section. The Corps Signals Officer considered that the Section was part of his organization. . . In his view they were Signals personnel performing Intelligence duties, rather than Intelligence personnel attached to a Signals unit for administrative and operational convenience.[40]

Brigadier Foulkes, BGS First Canadian Army, finally rectified this ongoing debate in his First Canadian Army Intelligence Directive No. 4, issued 10 June 43. Obviously aware of disharmony within the Special Wireless units, he forcefully stated: "It is essential that all Special Wireless and Wireless Intelligence Sections should consider themselves as ONE UNIT and work in complete co-ordination and community of interest for one purpose only: TO PRODUCE INTELLIGENCE."[41]

By 19 August 1942, three Army Special Wireless Units had been mobilized in Canada and were now in England in various stages of embarkation, training, or collection operations.[42] The first to arrive, No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'B' - a Corps level unit - was conducting round-the-clock intercept and direction finding operations, in close cooperation with British 'sister' intercept units, against German military targets from Bolney, approximately 12 kilometers north of Brighton on England's south coast. Since their arrival in October 1941 soldiers of the unit had received approximately four weeks of specialized training, including lectures "on German and Italian procedure, the methods used to detect Control Station of nets, etc.," from the British Special Operators' Training Battalion (S.O.T.B.) at Trowbridge, Wiltshire, and had been operational since late December.[43] Of note, on the same day as the arrival of No. 2 Special Wireless Section to England, the unit "assisted the operation [at Dieppe] by relaying information from the Germans back to [Canadian] Corps to aid them in keeping track of what the Germans were doing and what information they had on the Canadian troops."[44] No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'B' continued intercept operations in the south of England until deploying to Italy with 1st Canadian Corps Headquarters in early January 1944, where it served until March 1945.

|

| No. 1 S.W. Section at Bolney, 1941 |

It was while in Italy at the height of the Battle of the Liri Valley, that Signalman Ed Marten "intercepted a message from the Herman Goering [Panzer] Division indicating that it was on the move" in response to the Allied offensive of late May. This essential information, immediately recognized for its value and quickly passed through the intelligence chain, enabled a concentration of "all available fighters and fighter-bombers" to attack the German counter-attack force, "causing considerable losses."[45] No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'B' advanced northward through Italy with the Canadian Corps as far as Ravenna, when, in early March 1945, it was ordered to "turn in all its equipment" and join fellow Special Wireless Sections then supporting the First Canadian Army in Northwest Europe.[46]

Not so fortunate operationally was No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'C', under the command of Lieutenant G.A. Cooper, which formed under questionable circumstances in Ottawa in late June 1941.[47] The small unit - with a maximum strength of 23 all ranks, including one officer - lived, trained, and deployed to England together with No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'B', but it is evident from the unit's War Diary that it experienced difficulty acquiring personnel and equipment from the outset. Once in England the unit did not receive S.O.T.B training, as did the Type 'B' Section, nor did it deploy to the English south coast to conduct any operational mission. Notwithstanding these factors, however, from October 1941 until the unit was "reduced to zero strength" in late March 1942 on order of the Corps Chief Signal Officer (C.S.O.) Colonel Genet, Lieutenant Cooper and his men worked tenaciously to sustain themselves, and generate a mission capability.[48]

Interestingly, in early March 1942 the Canadian Signal Reinforcements Unit (C.S.R.U.) gainfully employed No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'C' as an ad-hoc 'friendly-force' monitoring element. Very quickly unit soldiers intercepted communication and operational security violations, most notably two unidentified English operators who "mentioned in clear several names of places as well as names of officers up to the rank of Colonel, and described in detail an area defence scheme of which they were a part, giving locations of H.Q. and other security information."[49] The incident was reported to the C.O. of the C.S.R.U. on 16 March: a mere 8 days later No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'C' effectively ceased to exist. As the frustrated O.C. caustically noted, "ever since this Unit was first organized there has been a doubt in the minds of the War Office as to whether this Unit was really necessary"[50]: it appears that in late March 1942, perhaps as a result of its recent monitoring success, it was not! No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'C' remained on the war establishment, although with no manpower, until 1 April 1943, when it was officially disbanded.

No. 2 Special Wireless Section Type 'B', mobilized at Kingston on 5 May 1942 with a wartime establishment of 2 Officers and 68 Other Ranks, was by early August en route England aboard His Majesty's Transport Cameronia. [51] After completing initial administrative routines at the C.S.R.U. in Farnborough, the unit joined its Canadian 'sister' section (No. 1) at Bolney by early September. Highlights of its time in England included personnel attendance on the now expanded two-month S.O.T.B. 'Y' course at Trowbridge, and operational intercept and direction finding against German Army targets from various locations on the south coast. In the spring of 1943, Captain Bill Grant, the unit's first Officer Commanding, was sent to North Africa with the First British Army to gain battlefield 'Y' experience (command passed to his brother Captain Bob Grant).[52] Upon his return from North Africa, he was appointed G.S.O.3(I(s)) First Canadian Army, and thus became, in cooperation with a small Intelligence cadre at Army H.Q., responsible for all 'Y' issues within the Canadian Army.

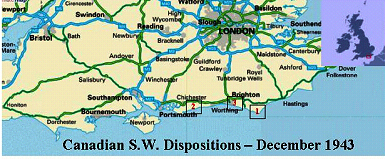

Prior to the departure to Italy of No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'B' in January 1944, there were three active Canadian Special Wireless Sections in England conducting real-time intercept operations against German military targets. No. 3 Special Wireless Section Type 'A', with Capt J.W. Anderson as O.C. and Lt. G.A. Cooper as his second-in-command, was formed in England in June of 1943 to provide "[g]eneral interception which provides Wireless Intelligence for the General Staff Intelligence at army HQ and "Y" information of value to other "Y" units."[53] The soldiers undertook British Army Special Operators training, but not at Trowbridge; No. 3 Section received their special wireless training from the S.O.T.B at Douglas, on the Isle of Man.[54] The unit commenced limited intercept operations in November 1943, and by December, all three Canadian Special Wireless Sections were integrated within 21st Army Group's Special Wireless collection network, tactically dispersed along the south coast of England[55]: No. 1 S.W. Section Type 'B' was located at Eastbourne, East Sussex; No. 2 S.W. Section Type 'B' was at Angmering-on-Sea, West Sussex; and No. 3 S. W. Section Type 'A' was at Rottingdean, West Sussex. All of the 21st Army Group Special Wireless Sections were linked by both telephone and wireless. Despatch Riders (D.R.s) collected the intercept material from each unit daily - on occasion as often as four times per day - in order to transport it to London for further analysis/decryption (this material was concurrently provided through the chain-of-command to Corps and Army H.Q.). Purposefully, by December 1943, Canadian Special Wireless Sections were actively intercepting, analyzing and providing order-of-battle (O.O.B.) information on German units in France that they and the Canadian Army would face in 1944.

|

On 6 June 1944, No. 2 Special Wireless Section Type 'B' continued its intercept and direction-finding mission from Pett Level, Sussex, while No. 3 Special Wireless Section Type 'B' was non-operational at Rustington, fully packed and loaded for its transfer to France.[56] Both units were on the European continent supporting their Corps and Army Headquarters by 17 July: No. 2 Section from Cairon, and No. 3 Section from Amblie, approximately 15 kilometres distant. Section intercept sites were located in the rear of the battle area near their respective H.Q.s, while their direction-finding detachments were dispersed well forward near the fighting echelon units. [57] Early intercept successes were frequent, such as No. 2 Special Wireless Section Type 'B's accomplishments against the 21st Panzer Reconnaissance Regiment, the "eyes of General Rommel": It was a German armoured car unit which. . . had fanned out across his entire front. Their communications leap-frogged all the normal communications echelons to report directly to him on the state of battle. They used a TL code. We could identify the unit immediately and read the code. We felt we were clearing the German messages to the 2nd Canadian Corps Headquarters faster than the Germans were to Rommel.[58] Both Special Wireless units supported all First Canadian Army Operations through France and into Belgium over the summer and fall of 1944. In addition, special composite detachments, involving soldiers from both Canadian and British S.W. sections of 21st Army Group, were frequently formed and assigned to specific intercept missions along the advancing Front (it is evident from both No. 2 and No. 3 S.W. Section war diaries that short-range 'line-of-sight' Very High Frequency (V.H.F.) radio transmissions, emanating from elite German units, were high-priority targets, although initial success against these elements was limited).[59] By December 1944, No. 2 and No. 3 S.W. Sections were operationally static in the Low Countries, deployed across the First Canadian Army frontage in Holland oriented facing eastward from Wijchen (approx 10 kilometres southwest of Nijmegen - No. 2 S.W. Section) in the north, to Tilburg (No. 3. S.W. Section) in the south. Also during this month, Major Bowes, the O.C. of No. 1 S.W. Section currently in Italy, conducted an initial reconnaissance to the area in preparation for his unit's return to the First Canadian Army in the spring of 1945.

|

| No. 2 S.W. Section near Nijmegen, Jan 45 |

Through the winter and spring of 1945, the Canadian S.W. sections fully followed General Foulkes Intelligence directive of June 1943, providing both "forward interception of strategical material for research at GHQ", and "providing information of direct interest at corps"[60]: they participated in OPERATIONs VERITABLE (in support of British 30 Corps), BLOCKBUSTER and PLUNDER. During OP VERITABLE they experienced success against 3 Panzer Grenadier Division, 20 Parachute Regiment of 7 Parachute Division, and 116 Panzer Division.[61] On 9 March (OP BLOCKBUSTER), Canadians intercepted and reported on German plain-language traffic that indicated the evacuation of German artillery units withdrawing eastward across the Rhine River in the area of Wesel: "[t]his extra ordinary msg specified units and gave total number of guns still in bridgehead."[62] On OP PLUNDER, Canadian Special Wireless provided accurate intelligence on the dispositions, mostly from plain-language intercept, of "6, 7, 8 PARA DIVS and 116 Pz Div Recce."[63] During this approximately two month period, F.H. Hinsley, editor of British Intelligence in the Second World War, Volume 3, notes: "Y enjoyed a marked revival. VHF links, especially those of the Parachute divisions, supplied a steady flow of information, mostly in plain language, to forward Sigint units."[64] The three Canadian Special Wireless Sections were reunited in late March of 1945 when the 1st Canadian Corps (including No. 1 S.W. Section Type 'B') joined the First Canadian Army. At the cessation of hostilities on 8 May, the Sections were located as follows: No. 1 S.W. Section was in Holland in the area of Apeldoorn; No.'s 2 and 3 S.W. Sections were in Germany in the areas of Bad Zwifchenahn and Meppen respectively. The units continued to monitor enemy frequencies subsequent to 8 May to ensure German compliance to the surrender, while at the same time plan for the eventual repatriation to Canada of their soldiers.

No Canadian Special Wireless soldiers were killed by enemy action in Northwest Europe (a small number did die of accident or illness), however, there were countless close calls as the units moved with the First Canadian Army through France, Belgium, Holland and Germany in the fall of 1944 and spring of 1945. Most involved unit reconnaissance activity, such as the time when "Capt Grant GSO III (Is) and Cpl Patenaude had a bit of a scare . . . when they wandered a couple of hundred yards out in front of #2 Det [DF] site and drew a half a dozen 88 mm sheels [sic] from Jerry"[65]; but there were other occasions including but not limited to a "VHF det. receiv[ing] [a] near hit by American bombers"[66] and flying bombs (V1, V2) landing very near the billets of No. 3 S.W. Section when the unit was located in Antwerp.[67]

The Pacific

As Canadian Special Wireless Sections traversed through France and into the Low Countries in the summer and fall of 1944, a new much larger S.W. unit was being formed in Canada for service in the Far East. In May of that year, the Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army requested that Canada "supply a special Signals and Intelligence Unit. . . to intercept transmissions from Tokyo which could not be heard in Canada."[68] The Minister of Defence approved authorization for the formation of such a unit, No. 1 Special Wireless Group[69], on 19 July; however, due to ongoing manpower shortages, mobilization was slow. Original Canadian intent was to send a first draft of S.W. Group soldiers to India by 1 October, with the second draft departing approximately two months later - in actuality, the unit did not deploy until mid-January 1945, and by then their destination had been amended from India, to Australia. [70]

Soldiers were drawn from available manpower pools of the Military Districts (M.D.s) across Canada, and included volunteers from each of the Special Wireless Stations. Intelligence specialists were recruited from the first "Army Japanese Language School in Vancouver." [71] Training took place in Ottawa and at secretive locations on Vancouver Island outside of Victoria - Patricia ('Pat') Bay and Gordon Head.[72] It would be the intercept operator's function to copy military "Kana code", a Japanese adaptation of Morse code, while the Intelligence section would provide the translation and analysis.[73] The unit was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel H.D.W. Wethey, the first Officer Commanding of the small Special Wireless element created at Rockliffe in 1939.

After nearly a month at sea on board United States Transport ships, the entire unit disembarked at Brisbane on 16 February 1945 and spent the next two months coordinating issues with their Australian and American 'Y' counterparts from 'Camp Chermside', a bustling 400-acre military encampment on the outskirts of the city.[74] It was during this time that a decision was made to locate the 'Group' at Darwin - on Australia's north coast - to work in concert with other Allied 'Y' units in that region, and plans were drawn up for the move. Operationally the Canadians would be responsible to the joint Australian/U.S. 'Central Bureau', General Douglas MacArthur's signal intelligence centre in the Pacific. The unit move north took place via rail and road transport over a two-week period in early April, and by mid-May 1945 the site, constructed on a reclaimed 'swamp' on MacMillan Road, was operational, with operators manning 13 intercept positions on a 24-hour a day basis.[75]

No. 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group contributed a tremendous amount of intercepted material to the Allied SIGINT effort in Australia. Less than a month after commencing full-time operations, the Canadians were responsible for approximately 22% of all messages intercepted by the 12 Allied sites (4 U.S., 7 Australian, 1 Canadian) on the continent.[76] Intelligence Section personnel, recognized for their strong abilities in Japanese, were frequently requested by other units; by late July nine personnel under the leadership of Captain Woodsworth were working for a Central Bureau detachment in Manilla, Phillipines, and one - Sgt Olmstead - was in San Miguel.[77]

Not surprisingly, and in a very Canadian fashion, the site on MacMillan Road did more than conduct intercept operations against Japanese military targets. Very quickly, due to initiatives at all levels of command, the Camp became a hive of social activity for Australian and U.S. personnel working in the area. A quickly constructed large-screen outdoor theatre, where movies such as Errol Flynn's 'Objective Burma' were shown thrice weekly - courtesy of "the U.S. Signal Corps" - drew crowds in excess of 2000 people![78] An inter-service baseball league was organized; a 'choral society' of Canadian soldiers regularly entertained, often accompanied by the unit 'orchestra'; Canadian dances became events to attend, and a 'newspaper club'- The Static Press - provided weekly items of interest.[79] In a very short period of time, the Canadians certainly contributed to and positively impacted morale on Australia's north coast.

Following the surrender of Japan mid-August, No. 1 Canadian S.W. Group began preparations for a return home. Administrative and logistic delays plagued the unit throughout the fall, and it remained in Australia until February 1946, when its soldiers finally boarded a troop ship for their return to Canada. While the patience of the soldiers to return home was often tested, their ultimate efforts were recognized by Lieutenant-Colonel Wethey, as he remarked in the unit's Souvenir Booklet:

Despite the relatively short time the Unit has been in existence a very great deal has been accomplished. Not only has the operational role of the Unit been performed in a manner which has received due recognition, but your industry and perseverance in the prosecution of tasks not normally required of a Unit such as ours have enabled us to play our part in the defeat of Japan much earlier than might otherwise have been expected.[80]

Before their release from the Army; however, No. 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group soldiers were once again reminded "of their oath of secrecy - to never reveal their wartime duties. Not even to family."[81]

Conclusion

For over 40 years, the soldiers of No. 1 S.W. Group followed to the letter the final direction they received from their chain-of-command - not to reveal their wartime activities to anyone. So to did their fellow 'Special Wireless' soldiers who served in Canada and Europe during the Second World War. The success of their silence is attested to by the dearth of information about their activities found in the histories of the two Canadian Army organizations who provided the personnel - the History of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals 1903-1961, edited by John S. Moir, and Scarlet to Green: A History of Intelligence in the Canadian Army 1903-1963, by Major Stuart Elliot. The first work contains less than a paragraph of information about 'Special Wireless' in the entire volume; the second, while it does provide more detail, is still quite sparse on the subject.

Tireless dedication to the mission, unit and individual ingenuity, recognition by the soldiers of the value of their work in saving Canadian lives while at the same time aiding to defeat the enemy, and understanding the absolute necessity to protect the secrecy of their operations characterize Canadian Special Wireless operations in Canada, Europe and the Pacific theatre during the Second World War. Perhaps Major Bowes, O.C. No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'B', best summarizes Canadian SIGINT efforts of the War when, upon his unit's return from Italy in March 1945, he wrote: Even though our achievements and successes have not, and never will be, brought to the attention of the public, as have the brilliant exploits of our brother-in-arms who are serving in Canada's traditional regiments, we have the satisfaction of knowing that our efforts have greatly helped in the bringing about of the downfall of the most ruthless military power the world has ever known.[82]

The fact that the Canadian Forces continues to have a thriving 'SIGINT' organization in the 21st century is tribute to the efforts of men such as Lieutenant-Colonel Ed Drake and Captains Bill and Bob Grant, and the hundreds of men and women who served their country in 'Special Wireless' during the Second World War. More needs to be written on this subject.

Endnotes

- ↑ Wesley K. Wark, "Cryptographic Innocence: The Origins of Signals Intelligence in Canada in the Second World War," Journal of Contemporary History, Vol 22. No 4, October 1987, London: SAGE Publications, 1987, pp 643-44. Wireless intelligence (now known as COMINT - communications intelligence, a subset of SIGINT) is the interception, analysis and reporting of foreign/enemy radio transmissions and its message contents. Throughout the war, it had various names, of which 'Special Wireless', 'Y' work and 'Radio Intelligence' are the most prevalent.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 664.

- ↑ 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group soldiers serving in Australia did not depart for Canada until February 1946, War Diary, 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group, 7 February 1946, CD-ROM Collection, Communications & Electronics Museum Archives, Kingston, ON. p. 3.

- ↑ W. Arthur Steel, Captain, "General Report on Wireless Telegraph Communication Canadian Corps Feb 1915-Dec 1918," National Archives of Canada, 16 April 1919, Accessed 1 February 2004, , p. 10. The particular intercept objective of this site was German short range Company to Battalion wireless communications.

- ↑ W. Arthur Steel, Major, "Wireless Telegraphy in the Canadian Corps in France - Interception - I Toc and Policing Work, Wireless Interception in the Canadian Corps," Canadian Defence Quarterly, Vol VII, October, 1929, to July, 1930, Ottawa: Runge Press, 1930, p. 372. Non-wireless intercept operations were labeled "I Toc" work

- ↑ W. Arthur Steel, Lieutenant-Colonel, "Wireless Telegraphy in the Canadian Corps in France," Canadian Defence Quarterly, Vol VIII, October, 1930, to July, 1931, Ottawa: Runge Press, 1931, p. 91. Between site opening on 15 August and closure on 21 August, an average of 30 messages per day was intercepted. Canadian Corps Staff immediately received copies of all intercepts, with priority messages being sent by wire to "Intelligence "E" Fourth Army." I can find no reference to wireless intercept being conducted by the Canadians during subsequent pursuit operations.

- ↑ John S. Moir, (Ed.), History of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, 1903-1961, Ottawa: Corps Committee Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, 1962, p. 38.

- ↑ Steel, "Wireless Telegraphy in the Canadian Corps in France - Interception," pp. 366, 374.

- ↑ Earl Bryden, Chief Warrant Officer, History of Canadian Military SIGINT, Minute Sheet of Major Dave Lawrence, OC E Sqn, Kingston, File No 1326-1, 15 Apr 1991.

- ↑ John Bryden, Best-Kept Secret: Canadian Secret Intelligence in the Second World War, Toronto: Lester Publishing, 1993, p. 8. Royal Canadian Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force wireless intelligence operations during the war are outside the scope of this paper.

- ↑ S.R. Elliot, Major, Scarlet to Green: A History of Intelligence in the Canadian Army 1903-1963, Toronto: Canadian Intelligence and Security Association, 1981, p. 460.

- ↑ Norman A. Weir, Captain, (Ed.), "Second World War Canadian Army Signal Intelligence Experiences of Major R.S. Grant, MBE, CD," Communications and Electronics Newsletter 1986 - Special Wireless Edition, Ottawa: DGCEEM, 1986, p. 5. Capt Bob Grant and his brother, Capt Bill Grant, both served in Canadian Special Wireless units throughout the war.

- ↑ Bryden, Best-Kept Secret, p. 14. Capt Wethey was in England within the first month of the unit's existence. Britain had a well developed, although highly secretive SIGINT capability at the time, which operated under the guise of the Government Code and Cipher School (GC & CS).

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 16-17. Operational control of the Rockliffe site was quickly transferred to Military Intelligence, while the Signal Corps continued to provide the intercept operators. To avoid duplication of effort, coverage of targets of interest was coordinated between the two countries.

- ↑ Canadian Forces Station Leitrim, the Canadian Forces SIGINT centre, celebrated its 60th Anniversary on 8 June 2001.

- ↑ Bryden, Best-Kept Secret, p. 26.

- ↑ Wark, Cryptographic Innocence, p. 643.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ G. de B. Robinson, Ed., A History of the Examination Unit 1941-1945, Ottawa: Examination Unit Staff, 1945, pp. 11-16. The Examination Unit is the predecessor of Canada's current SIGINT organization, the Communications Security Establishment (C.S.E.).

- ↑ Ibid., p. 4.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 4-9.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 16.

- ↑ Bryden, Best-Kept Secret, pp. 72-95.

- ↑ Robinson, A History of the Examination Unit, p. ii.

- ↑ Bryden, Best-Kept Secret, p. 99. This would become No 3 Special Wireless Station.

- ↑ War Diary, No. 2 Special Wireless Station, 8 May 42. CD-ROM Collection, Communications & Electronics Museum Archives, Kingston, ON.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 1. By October 1944, the station had a strength of 39 all ranks. During the same month, Leitrim had 66 all ranks (including 13 members of the Canadian Women's Army Corps - C.W.A.C.s). If Victoria had manning approximately equal to Grande Prairie (smaller stations than the original at Leitrim), during the latter half of 1944, it may be assumed that the Army had approximately 150 personnel employed at static Special Wireless collection sites in Canada. Assuming 24 hour a day intercept operations and a manning ratio of 4:1 (4 operators to one intercept position), it is possible that the Army may have collectively manned as many as 37-40 intercept positions against enemy targets at the height of the war.

- ↑ Hans Legere, #4 Special Wireless Station - Riske Creek, Undated, Accessed 15 Feb 2004, . Little information is available on either No. 3 or No. 4 Special Wireless Stations. The closure of Riske Creek may be attributed to the establishment of 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group for service in the Pacific theatre in July 1944.

- ↑ War Diary, No. 2 Special Wireless Station, 25 August 43.

- ↑ David Alvarez, (Ed.), Allied and Axis Signals Intelligence in World War II, London: Frank Cass Publishers, 1999, p. 53.

- ↑ Elliot, Scarlet to Green, p. 426; see also Bryden, Best-Kept Secret, pp. 142-43.

- ↑ Bryden, Best-Kept Secret, p. 126. Attending from Canada were Captain Drake (Army), Colonel Murray (Director of Military Intelligence), and Commander Jock de Marbois (R.N. - representing the Canadian Navy's Operational Intelligence Centre).

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 161-167.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 133.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 227-228. The 1944 Arlington Conference formed the basis for post-war SIGINT sharing between the Allies.

- ↑ War Diary, Special Wireless Section Type "B". R.C. SIGS. (A.F.), December 1940, CD-ROM Collection, Communications & Electronics Museum Archives, Kingston, ON.

- ↑ Elliot, Scarlet to Green, p. 127.

- ↑ Charles Foulkes, BGen, "First Canadian Army Directive No. 4 Instruction on the Training, Control and Employment of Wireless Interception (Y) Organization in the Field, 1 Jun 43," cited in Communications and Electronics Newsletter 1986 - Special Wireless Edition, Ottawa: DGCEEM, 1986, p. 42.

- ↑ Weir, "Second World War Canadian Army Signal Intelligence Experiences of Major R.S. Grant," p. 8.

- ↑ Elliot, Scarlet to Green, p. 126. Tension between Signals and Intelligence personnel in Electronic Warfare (EW), the successor of Special Wireless in the Canadian Army, remains prevalent today.

- ↑ Weir, "Second World War Canadian Army Signal Intelligence Experiences of Major R.S. Grant," p. 42.

- ↑ War Diary, No. 2 Special Wireless Section Type 'B', 19 August 1942. Initial training of Army Special Wireless Units in Canada had been conducted at the 'Cow Palace' at Lansdowne Park, and with the Special Wireless Station at Rockliffe and later Leitrim.

- ↑ War Diary, No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'B', November - December 1941, CD-ROM Collection, Communications & Electronics Museum Archives, Kingston, ON. A very close working relationship with tactical British 'Y' operators and organizations that continued throughout the war may be considered to stem from this initial training period.

- ↑ C.J. Weicker, Col, "The Original Canadian "Spies of the Airwaves: The Untold Story of Number 1 Canadian Special Wireless Section Type "B"," Communication & Electronics Newsletter, Vol 44, July 2002, Accessed 12 January 2004, .

- ↑ Ibid; see also Sidney T. Matthews, General Clark's Decision to Drive on Rome, undated, Accessed 15 February 2004, p. 362. Although this second reference does not involve intelligence, it does state "the Herman Goering Division actually had been severely damaged by Allied air attacks en route to the south. . ."

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ War Diary, No. 1 Special Wireless Section Type 'C', June 1941. CD-ROM Collection, Communications & Electronics Museum Archives, Kingston, ON. No War Establishment reference is included in the introductory page to the War Diary, as is the case with the other Special Wireless units. I have found no reference to Type 'C' units in available material, but due to size and composition, assume that it may have been formed ad-hoc to provide Divisional-level support (Type 'A' = Army, Type 'B' = Corps, Type 'C' = Division?).

- ↑ Ibid., 24 March 1942.

- ↑ Ibid., 16 March 1942.

- ↑ Ibid., 24 March 1942.

- ↑ War Diary, No. 2 Special Wireless Section Type "B", 1 August 42. The two officers were recently commissioned brothers, Capts Bob and Bill Grant, who were initially noted as two of the first intercept operators at the fledgling Army Wireless site at Rockliffe in 1939.

- ↑ Weir, "Second World War Canadian Army Signal Intelligence Experiences of Major R.S. Grant," p. 6. Captain W.E. Grant does not show up in the C.M.H.Q. report of Canadians attached to the First British Army in Tunisia - 1942-1943; due to the secretive nature of the work, he was probably "sent to the African theatre under special arrangements" (see LCol Stacey, Report No. 95 Historical Officer, Canadian Military Headquarters, Attachment of Canadian Officers and Soldiers to First British Army in Tunisia - 1942 - 1943, dated 18 Mar 46). Capt Grant rejoined No. 3 S.W. Section in the late fall of 1944.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 43. This unit initially had a complement of 2 Officers and 75 Other Ranks, drawn from the Canadian Signal Reinforcements Unit. During the initial mobilization phase, there was a substantial amount of cross-posting from the two Canadian Type 'B' sections. In August 43, Special Wireless soldiers were recognized in the war establishment as 'Operators Special' vice previous designation as "Operators Wireless and Line."

- ↑ War Diary, No. 3 Canadian Special Wireless Section Type 'A', 24 August 43, CD-ROM Collection, Communications & Electronics Museum Archives, Kingston, ON.

- ↑ Ibid., November 1943. 21st Army Group included at least the following S. W. Units: British - No. 1 S.W. Group, No. 8 S.W. Section Type 'A', No. 104 S.W. Section Type 'B', and No. 112 S.W. Section Type 'B'; Canadian - No. 1 S.W. Section Type 'B', No. 2 S.W. Section Type 'B' and No. 3 S.W. Section Type 'A'.

- ↑ No.'s 2 and 3 Special Wireless Section War Diaries, 6 Jun 1944.

- ↑ Ibid., 17 July 1944. The Canadian Sections joined the 21st Army Group Special Wireless net on 19 July, which, at the time, included No's 8, 109, and 110 Special Wireless Sections.

- ↑ Weir, "Second World War Canadian Army Signal Intelligence Experiences of Major R.S. Grant," p. 18.

- ↑ War Diary, No. 3 S.W. Section, 27-31 July 1944. The German's felt - incorrectly - that V.H.F. communications were not as susceptible to intercept.

- ↑ Weir, "Second World War Canadian Army Signal Intelligence Experiences of Major R.S. Grant," p. 43.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 63.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 68.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 70.

- ↑ F.H. Hinsley, (Ed), British Intelligence in the Second World War, Its Influence on Strategy and Operations, Volume 3 Part II, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988, p. 677.

- ↑ War Diary, No. 3 Special Wireless Section, 24 July 1944.

- ↑ War Diary, No. 2 Special Wireless Section, 8 August 1944.

- ↑ War Diary, No. 3 Special Wireless Section, 12-30 October 1944.

- ↑ Elliot, Scarlet to Green, pp. 384-85.

- ↑ A Special Wireless Group usually supported an Army Group. Established strength of the Signal element was 13 officers and 278 men; the Wireless Intelligence Section was to be 6 officers and 41 men - total strength of No. 1 S.W. Group was 329 all ranks.

- ↑ Elliot, Scarlet to Green, pp. 384-85.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 384.

- ↑ Gil Murray, The Invisible War: The Untold Secret Story of Number One Canadian Special Wireless Group, Royal Canadian Signal Corps, 1944-1946, Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2001.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 37-39.

- ↑ War Diary, No. 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group, February 1945; for a description of Camp Chermside see Peter Dunn, Australia @ War, 23 January 2004, Accessed 20 February 2004

- ↑ Ibid., April-May 1945.

- ↑ Jamie McCaffrey, "1 Canadian Special Wireless Group," Communications and Electronics Newsletter, Vol 41, October 2000, Accessed 20 February 2004,

- ↑ War Diary, No. 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group, 1 August 1945.

- ↑ Ibid., 26 July 1945.

- ↑ Mel Howey, (Ed), 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group Royal Canadian Corps of Signals Souvenir Booklet, 1944-45, Darwin: 1945, pp. 6-23.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 1.

- ↑ McCaffrey, "1 Canadian Special Wireless Group," p. 2.

- ↑ Weicker, "The Original Canadian "Spies of the Airwaves"", p. 13.

References

Alvarez, David. (Ed). Allied and Axis Signals Intelligence in World War II. London: Frank Cass Publishers, 1999.

Bryden, Earl. Chief Warrant Officer. History of Canadian Military SIGINT. Minute Sheet of Major Dave Lawrence, OC E Sqn, Kingston, File No 1326-1, 15 Apr 1991.

Bryden, John. Best Kept Secret: Canadian Secret Intelligence in the Second World War. Toronto: Lester Publishing, 1993.

Dunn, Peter. Australia @ War. 23 January 2004. Accessed 20 February 2004.

Elliot, S.R. Scarlet to Green : A History of Intelligence in the Canadian Army, 1903-1963. Toronto: Canadian Intelligence and Security Association, 1981.

Hinsley, F.H. (Ed). British Intelligence in the Second World War. Vol 3. Part II. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Howey, Mel. (Ed). 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals Souvenir Booklet, 1944-45. Darwin: Unit Staff, 1945.

Legere, Hans. #4 Special Wireless Station - Riske Creek. Undated. Accessed 15 February 2004. .

Matthews, Sidney T. General Clark's Decision to Drive on Rome. Undated. Accessed 15 February 2004. .

McCaffrey, Jamie. Sgt. "1 Canadian Special Wireless Group." Communications and Electronics Newsletter. Vol 41. October 2000. Accessed 20 February 2004. .

Moir, John S. (Ed). History of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, 1903-1961. Ottawa: Corps Committee royal Canadian Corps of Signals, 1962.

Murray, Gil. The invisible war : the untold secret story of Number One Canadian Special Wireless Group, Royal Canadian Signal Corps, 1944-1946. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2001.

Robinson, G. de B. A History of the Examination Unit 1941 - 1945. Communication Security Establishment Archives. Ottawa: Examination Unit Staff, 1945.

Steel, W. Arthur. Captain. "General Report on Wireless Telegraph Communication Canadian Corps Feb 1915-Dec 1918." National Archives of Canada. 16 April 1919. Accessed 1 February 2004. .

Steel, W. Arthur. Major. "Wireless Telegraphy in the Canadian Corps in France - Interception - I Toc and Policing Work, Wireless Interception in the Canadian Corps." Canadian Defence Quarterly. Vol VII. October, 1929, to July, 1930. Ottawa: Runge Press, 1930.

Steel, W. Arthur. Lieutenant-Colonel. "Wireless Telegraphy in the Canadian Corps in France." Canadian Defence Quarterly. Vol VIII, October, 1930, to July, 1931. Ottawa: Runge Press, 1931.

War Diary, No. 1 Canadian Special Wireless Group. July 1944 - February 1946. CD-ROM Collection. Communications & Electronics Museum Archives. Kingston, ON.

War Diary, No. 1 Canadian Special Wireless Section Type 'B'. December 1940 - December 1941, July 1941 - January 1942. CD-ROM Collection. Communications & Electronics Museum Archives. Kingston, ON.

War Diary, No. 1 Canadian Special Wireless Section Type 'C'. June 1941 - April 1942. CD-ROM Collection. Communications & Electronics Museum Archives. Kingston, ON.

War Diary, No. 2 Canadian Special Wireless Section Type 'B'. August 1942 - July 1945. CD-ROM Collection. Communications & Electronics Museum Archives. Kingston, ON.

War Diary, No. 3 Canadian Special Wireless Section Type 'A'. June 1943 - July 1945. Communications & Electronics Museum Archives. Kingston, ON.

Wark, Wesley K. "Cryptographic Innocence: The Origins of Signals Intelligence in Canada in the Second World War." Journal of Contemporary History. Vol 22. No 4. October 1987. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1987.

Weicker, C.J. Colonel. "The Original Canadian "Spies of the Airwaves": The Untold Story of Number 1 Canadina special Wireless Section Type "B"." Communication & Electronics Newsletter. Vol 44. July 2002. Accessed 12 January 2004.

Weir, Captain Norman A. (Ed). "Second World War Canadian Army Signal Intelligence Experiences of Major R. S. Grant, MBE, CD." Canadian Forces Communications and Electronics Newsletter, 1986, Special Wireless Edition. Ottawa: NDHQ, 1986.