RCSigs perspective on CAFATTT

By: Rick Spencer (Major Retired) February 21, 2014

Contents

- 1 The Mission

- 2 Why and how we got into Tanzania

- 3 The Deployment of CAFATTT

- 4 Signals History in CAFATTT 1965 – 1970

- 5 Climate

- 6 Sites to See in Tanzania

- 7 Recreation

- 8 Leave

- 9 Medical Care

- 10 Working Hours

- 11 A Fond Farewell

- 12 My Colleagues

- 13 Summary

- 14 ANNEX A: A testimonial on CAFATTT by Lieutenant Colonel Art Beemer

- 15 ANNEX B: A testimonial on CAFATTT by Al Currie (Captain retired)

- 16 ANNEX C: A testimonial on CAFATT by Larry Hooper, Foreman of Signals

- 17 ANNEX D: A testimonial on my tour in Tanzania by Gerry Watt

- 18 ANNEX E: A testimonial on CAFATTT by Carl J. Arthurs (Master Warrant Officer Retired)

- 19 ANNEX F: A testimonial on CAFATTT by Bill Fleet (Master Warrant Officer Retired)

- 20 See Also

- 21 References

The Mission

The Canadian Armed Forces Advisory and Training Team Tanzania (CAFATTT) was officially authorized on December 8th, 1964. Over the next five years the Canadian military contingent was tasked to build the Tanzanian People's Defence Force (TPDF) from the ground up, creating everything from Tanzania's National Defence Act to the instructional pamphlets used for teaching weapons classes and all of the necessary systems in between including administration, financial, logistics, communications, training and so on.

Why and how we got into Tanzania

Tanzania made a formal request for military assistance to Ottawa in April 1963, but the Minister of National Defence, Paul Hellyer, in the midst of a departmental re-structuring exercise, was adamant that nothing could be done. Even when the President of Tanzania, Julius Nyerere, subsequently raised the issue of Canadian military assistance with the prime minister, Lester Pearson, during a state visit to Canada in July 1963, the Department of National Defence (DND) insisted the government not make any commitment to provide a training team similar to the one in Ghana. Therefore, it was not until summer 1964 that the Canadian Forces were finally directed, by Prime Minister Pearson, to send a survey team to Dar es Salaam.

Heated debate between the Department of External Affairs (DEA), The Department of National Defence (DND), Finance, and the Department of Defence Production (DDP) eventually led to a feasible solution whereby all parties participated in an interdepartmental Military Assistance Committee (MAC) that would share control over budgets and programs. The MAC determined how requests for aid would be fulfilled and then forwarded proposals and budget costs to the Cabinet Committee on External Affairs and Defence (CCEAD) for approval. With a satisfactory mechanism in place DEA was able to renew their efforts to procure military assistance for Tanzania.

The strategic function, particularly of the 83-man team in Tanzania, was to maintain a Western presence to counter Soviet and Chinese-bloc political and military influence. This Programme was disbanded in 1971, when the Trudeau government disavowed its strategic value. The original program was to provide unarmed military aircraft - Otters and Caribous - plus $10M in funding for a 5 year period. One of the reasons that the program was not extended was that we would not supply offensive weapons or equipment.

CAFATTT was seconded to the Department of External Affairs. Thusly, CAFATTT members, now being members of DEA, carried a green diplomatic passport. This entitled the team to travel first class because all DEA members travelled first class which was a nice bonus, particularly on those long flights over the Atlantic.

The Deployment of CAFATTT

With the decision to provide the requested assistance to Tanzania finalized, DND tasked the Canadian Forces Headquarters (CFHQ) to provide the advisory group and a training group for CAFATTT. The advisory group assignment was a two-year accompanied posting at the Tanzanian People's Defence Force (TPDF) headquarters in Dar es Salaam, while the training group assignment was a one-year unaccompanied posting at Colito Barracks. Colito Barracks was subsequently renamed Lugalo Barracks. Later the Tanzania Military Academy, TMA, was opened just outside of the Tanzanian capital, Dar es Salaam.

The details of the MAC plan for Tanzania were straightforward. Canada was to deploy a

team of approximately 30 advisory and training personnel to Tanzania. This number was increased to 83 with the addition of the Air Force support elements. The mission was to assist in the development of the Tanzanian defence and security forces. Part of the development of the Tanzanian defence and security forces was to also make places available for Tanzanians in Canadian military establishments and courses.

The advisory group worked with Brigadier General M.S.H. Sarakikya, the Tanzanian Chief of Defence Forces (CDF) to establish the foundations of what would become a new military. The training group prepared Colito Barracks to serve as the temporary military academy until the permanent academy was completed at Arusha. Colonel Price, the commander of CAFATTT, quickly discovered that there was much work to be done.

The TPDF had no National Defence Act (NDA), no military legal or logistics system, and no administrative capability. There were no service records for soldiers or any system to regulate and verify pay. Not a single qualified or experienced staff officer could be found in the Defence Force Headquarters (DFHQ), and there was not even a clerical staff to handle typing and filing. Everything had to be built up from scratch. The training group experienced similar challenges. The TPDF had no recognized training standards or system, and there were no training aids or instructional pamphlets for any of the trades.

The Tanzania Military Academy was initially organized into five wings with a staff of 250

personnel, including 18 Canadians. Each wing - administrative, basic training, officer training, battalion training, and technical training – was overseen by two Canadian members assisted by a small number of recently trained Tanzanian officers and soldiers. The objective was to provide direction while TPDF instructors were trained after which the Canadian positions could gradually be eliminated.

Throughout the CAFATTT mission both Russian and Chinese advisory teams, who were also competing to have influence in Tanzania, continuously challenged the Canadians, initiating a game of Cold War chess with all of Southern Africa as the prize. In the end, the Canadians were unable to sway Tanzania towards the west and were forced to leave only five years after we had first arrived.

Signals History in CAFATTT 1965 – 1970

When the Signals personnel arrived in Tanzania they, like the rest of the contingent, had to start from the ground up. They found that the radio and communications equipment was a mixture of equipment from various nations. There were no instructions, and most of the equipment was not in working condition. To their credit, the team improvised, adapted and overcame great difficulties to get the mission completed - as Canadians always do.

I arrived in Dar es Salaam, the capital of Tanzania, on the 1 May 1969 with four other Canadians; I was a radio technician at the time. After clearing Tanzanian Customs we were taken to Keko Flats and introduced to our new homes for the next year. I shared a suite with Sergeant Frank Richard, a Radio Operator. The Canadian quarters at Keko Flats were three identical buildings, as pictured below. The buildings were in a “U” shape layout. The center building was for the officers, the building on the left contained our Mess Hall. The building on the right had more personnel quarters and the Other Ranks Mess. Our meals were provided by a Canadian Service Corps Sergeant who was a Cook by trade. He supervised a full staff of Tanzanians. The cost of our meals was deducted from our pay on a monthly basis. Our quarters were cared for by Tanzanian “House Boys”. We contributed to their pay for any extra tasks they performed for us on a fee-for-service basis.

My work location was at TMA. When I arrived at TMA my first task was to try and determine where my predecessor had left off. There were not any written instructions or Standing Operating Procedures for me to follow. Consequently, I spent the next few days determining what exactly was expected of me and how I fitted into the Tanzanian technical training scheme of things. This was a common experience so, a handover period would have been appropriate. In the absence of clear terms of reference, I determined that my task was to supervise the Tanzanian military Instructors and instruct the Tanzanians in general communications and electronics theory, and equipment maintenance.

The only radios at our location were the USA RF-301 (AN/GRC 165) HF SSB (High Frequency Single Side Band) radios from Rochester, NY. When I arrived, some of the Radio sets were broken. There were not any maintenance manuals or technical specifications for this radio equipment. As these documents were essential for fault finding and maintenance in general, I wrote a letter to the company in Rochester, NY requesting technical manuals and schematic diagrams. In response, the company sent two of their technical personnel to assist with the repairs of the radios. At the same time they did some technical training with the Tanzanian instructors on these radios.

The training buildings were wooden structures with shutters for windows (no glass which is typical in Africa), and metal roofs. The absence of glass in the windows provides maximum ventilation to compensate for the heat and humidity but also permits access by all creatures, particularly flying creatures including bats, some of which are very large.

The electronic training aids were the same ones I had trained on in Canada (In fact, I suspect that they were the very same ones that I had my training on). The test equipment was modern and in good shape.

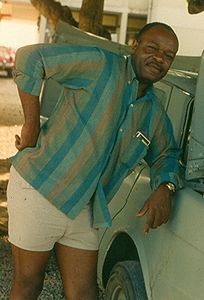

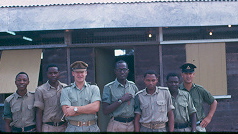

Captain Fred Heder, seen in the photo below, was the Canadian Signals Officer. He introduced me to the Tanzanian HQ and took me to TMA.

The Tanzanian students did very well on written exams but, their answers were rote, almost word for word from the book which told me that they did not fully understand the theory that they had been taught. My suspicions were confirmed when I saw that they were not able to practically apply their theoretical knowledge. In order to overcome this deficiency I developed some simple fault-finding tasks that required them to apply their new found theoretical knowledge while using their test equipment.

Africa has many customs and superstitions that westerners are not generally aware of; one such custom was; “don’t point at, or hand anything to a Tanzanian with the left hand”. Some consider this as an insult because they used their left hand to wash themselves with water as a substitute for toilet paper which traditionally had not been available to them. Unfortunately, I’m a left hander which can make things awkward in that circumstance! In order to preempt any inadvertently caused offence, I told the Tanzanian students and instructors about my left handedness. I asked them not to be offended if I pointed at them or handed them something with my left hand. They all took my situation in stride, smiled and had a good laugh about it!

During my time at TMA a new building was being constructed to house the long range HF Rhode & Swchartze Radio Transmitter & Receiver. After the equipment was installed (by a German contractor) I was tasked with erecting three 50 foot antenna towers. These towers can be seen in the picture on the right below.

- A new Communication building at TMA

Another Signals workshop was set up at Lugalo, to the north of the city. During my stay there the Teletype Technician, Sergeant Ray Searle, managed that shop. Sergeant Searle also trained the Tanzanians on teletype maintenance and fault-finding. Lugalo also doubled as a radio equipment repair shop. Accordingly, I was tasked to oversee Lugalo when Sergeant Searle returned to Canada. Just before I returned to Canada Lugalo received new Siemens T100 teletypes: Two Tanzanians soldiers had been trained on the T100 in Germany.

Climate

When I arrived at Dar es Salaam it was like stepping into a steam bath owing to the high humidity. On the first night, I remember that my bed sheets felt like they were damp, even though the room was semi-air conditioned; one window air-conditioner serviced the common area and the two adjacent bedrooms.

The weather was mostly sunny but also quite humid. To keep things dry I quickly learned to keep a light burning in the closet (wardrobe). I had taken my combat webbing with me and left it on top of the wardrobe; I checked it one day to find it covered with mold. Whenever it rained it was torrential but, the sun dried everything quickly; laundry could be washed, dried by the sun, and ironed by our house boys within an hour.

Sites to See in Tanzania

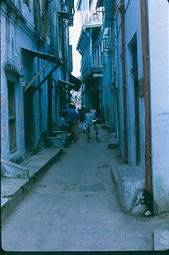

In Zanzibar the streets became very narrow towards the city center. Among other things, the shops on these narrow streets carried the famous and beautiful mahogany and brass Zanzibar chests that can be seen in the photographs below.

Bagamoyo is a small Arab community just north of Dar es Salaam. It is at the deepest indentation of the Indian Ocean into the east coast of Africa. This is where the infamous slave route ended. Pictured below is the building that imprisoned thousands of African Slaves before being loaded onto ships. The slaves were taken from the building to the ships via a tunnel. In the picture, Major Doug Roberts and his family are visiting the slave compound. Major Roberts was our Canadian Medical Officer (MO). Stanley and Livingston passed through Bagamoyo. Commonly, people believe that Stanley hacked his way through thick jungle to get to Livingstone. Actually, they went through bamboo thickets and savanna both of which also present challenges!

- The Slave compound in Bagamoyo

Lake Manyara National Park is another of Tanzania’s great natural treasures. Like the Serengeti, it has an abundance of wildlife and is safari heaven. Stretching for 50km along the base of the rusty-gold, 600-metre high Rift Valley escarpment, Lake Manyara is a scenic gem, with a setting extolled by Ernest Hemingway as “the loveliest I had seen in Africa”. There is no shortage of spring water for the forest and the abundant wildlife.

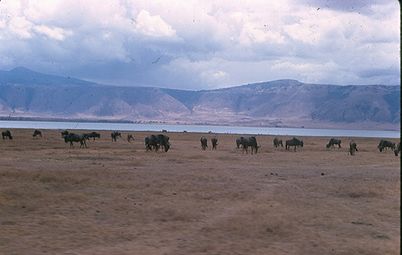

Ngorongoro Crater is an amazing Tanzanian game park and popular safari site. It is contiguous with the Serengeti to the Northwest. The crater was formed by the implosion of a huge volcano that collapsed into its self about two to three million years ago. The crater floor is about 20 kilometers in diameter (12.5 miles) and is rich with wildlife. Prior to the eruption it is estimated that the Ngorongoro volcano would have rivaled Mount Kilimanjaro in altitude. The rim of the crater can be seen in the pictures below as can the abundance of wildlife. Visitors to the crater were not allowed down into the crater without a park ranger for obvious reasons.

- Ngorongoro Crater

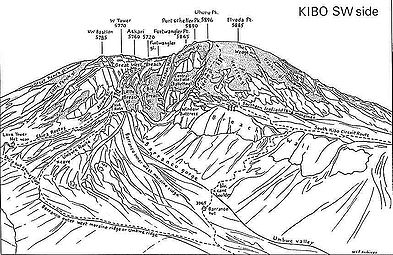

Mount Kilimanjaro is a dormant volcano which is composed of three distinct volcanic cones: Kibo 5,895 m (19,341 ft.); Mawenzi 5,149 m (16,893 ft.); and Shira 3,962 m (13,000 ft.). Uhuru Peak is the highest summit on Kibo's crater rim. It is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain in the world. Mawenzi and Shira are extinct, while Kibo, the highest, is dormant and could erupt again. The last eruption has been dated between 15,000 and 200,000 years ago. Although dormant, Kibo has gas-emitting fumaroles in its crater. Several members of CAFATTT have climbed this mountain during their tours in Tanzania.

- Mount Kilimanjaro

Recreation

Military personnel played volleyball in a court set-up in Keko Flats. Every Friday evening personnel from the Canadian High Commission would come to play volleyball which was followed by a BBQ. Occasionally, the “Live-in” personnel from Keko Flats would be invited to the Canadian High Commissioner’s residence, or to the commander of CAFATTT’s residence at Oyster Bay, for a sundowner”. A Sundowner was just a BBQ and drinks. Oyster Bay was the location of most of the CAFATTT personnel who had brought their wives and families with them. One Friday evening during volleyball the old cliché “It’s a small world” proved itself to be true. I heard my name being called and I turned to see Paul Shannon, a former Signals Soldier Apprentice from my intake. He was on staff at the High Commission as, Attaché-Head of Communications.

A dip in The Seamen swimming pool was refreshing after a hot day in the tropics.

- Mission to The Seamen’s Pool

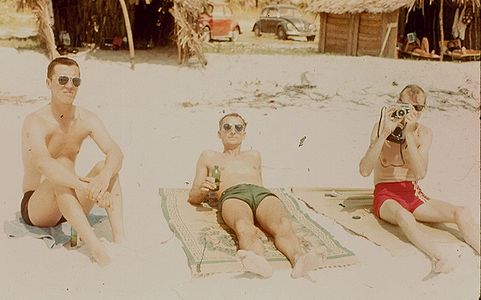

On weekends and holidays two beaches were visited by the Canadians, Silver Sands to the north and a deserted strip of beach to the south of Dar es Salaam.

- Beaches

Movie night was Sunday. Films flown in from Canada were projected onto a blank white outside wall on one of the buildings and we could watch them from our patio. The locals soon picked up on this and several dozen would sit in the courtyard to watch. This was a new experience to most of them and they got very excited during the action scenes.

Leave

Midway through the one year posting to CAFATTT, personnel were allowed four weeks leave. Most returned to Canada but, whatever one did, one had to ensure that one was out of the Tropic zone for health reasons.

Medical Care

There was a Canadian Medical Officer available as well as a Medical Corps Medical Assistant who lived-in at Keko Flats and ran the Medical Inspection Room (MIR). If personnel required hospitalization they went to the Civilian Hospital.

Due to the heat in the tropics we had to take a salt tablet daily and an anti-malaria pill every Friday. The salt tablets are used for nutritional support and to prevent heat prostration in hot climates among other things.

Working Hours

Working hours in tropical climates normally include a long mid-day break or siesta to avoid the intense heat. This cultural concept considered, the Canadians began operations daily at 7:30 am breaking for lunch at 12:00 pm. Class room activity ended at 3:00 pm. We did not take a long break at noon; rather, we shortened the work day slightly.

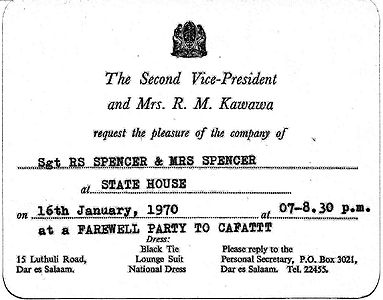

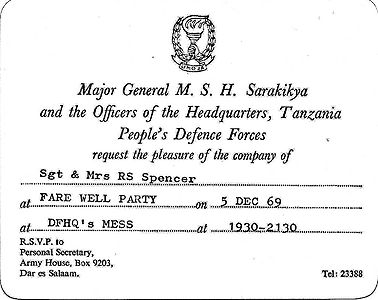

A Fond Farewell

I was among the last Canadians, to depart CAFATTT. Before our departure the Tanzanians formally said farewell to us with a couple of events that expressed their sincere thanks to Canada and all the members who had served on behalf of Tanzania. The formal invitations below were my personal invitations to these events:

My Colleagues

Some of my CAFATTT colleagues have shared their stories of their time in CAFATTT in the annexes that follow. The list of those Signals personnel that served in Tanzania is given in the table below. For ease of reference, the specific annex and page of their individual testimonials on CAFATTT is indicated in the Testimonial column.

Signals Personnel who served in CAFATTT (1965 – 1970)

| RANK (during tour) | NAME | INITIALS | TRADE | TESTIMONIAL | YEAR |

| Major | Beemer | A.J. | Signals | Annex A | 1967-1969 |

| Major | Bewely | D-Deceased | Signals | 1967-1968 | |

| Major | Kuspira | C-Deceased | Signals | 1965-1966 | |

| Captain | Kent | J- Deceased | Signals | 1965-1966 | |

| Major | Yerxa | D-Deceased | Signals | 1968-1969 | |

| Captain | Heder | F | Signals | 1969-1970 | |

| Staff Sergeant | Templeton | J | Comm Tech | 1965-1966 | |

| Staff Sergeant | Hooper | L | F of S | Annex C | 1966-1968 |

| Sergeant | Currie | A | R&Tg Op | Annex B | 1967-1968 |

| Sergeant | Owens | W | R&Tg Op | 1966-1967 | |

| Sergeant | Bagyan | W-Deceased | F of S | 1967-1968 | |

| Sergeant | Palmer | A | Rad Tech | 1968-1969 | |

| Sergeant | Spencer | R | F of S | Author | 1969-1970 |

| Sergeant | Watt | G | R&Tg Op | Annex D | 1968-1969 |

| Sergeant | Richard | F-Deceased | R&Tg Op | 1969-1970 | |

| Sergeant | Halal | R | R&Tg Op | 1965-1966 | |

| Sergeant | Arthurs | C | Tel Tech | Annex E | 1966-1967 |

| Sergeant | Fleet | W | Tel Tech | Annex F | 1966-1967 |

| Sergeant | Doran | J | R&Tg Op | 1965-1966 | |

| Sergeant | Quigley | K | Tel Tech | 1968-1969 | |

| Sergeant | Searle | R | Tel Tech | 1969 | |

| Sergeant | Parsons | L | F of S | 1965-1966 |

Summary

I regard my posting to CAFATTT as having been a distinct honour and a privilege. The opportunity to participate in the construction of the military of a foreign nation from the ground up was a unique experience that few Canadians had the opportunity to share. We all take the professionalism of the Canadian Forces for granted. But when the CAF of the time is juxtaposed with the then nascent state of the TPDF one can truly appreciate the huge task that was ahead. To put the job of CAFATTT into perspective, the experience of rebuilding the Canadian Forces after the disruption of the politically driven Integration and Unification of the three Canadian armed services in the late 60s was a parallel experience to our development from scratch of the TPDF. Just as those structures of the TPDF had to be built, the entire Canadian military, including the logistic, training, financial, occupational, organizational and administrative systems and structures had to be rebuilt including all manuals, orders, regulations and instructions necessary for their operation. Unfortunately, our mission was terminated before the job was done. Nevertheless, what we achieved in such a short time with so little was remarkable.

The progress that I could see at the end of my one year tour was impressive. At the same time, the experience of living in that natural wonder called Tanzania was a priceless experience. I would love to go back some day, perhaps on a safari.

VVV

Testimonials from other Canadians who served with CAFATTT follow in several annexes.

ANNEX A: A testimonial on CAFATTT by Lieutenant Colonel Art Beemer

Pre CAFATTT: In the mid 1960’s, when Canada agreed to help the Tanzanian military build their forces, I was the Squadron Commander of the Officer Training Squadron at the Royal Canadian School of Signals at Vimy Barracks in Kingston Ontario. There were several young Tanzanian officer cadets taking various communication courses within the squadron and they were accommodated at the Officers Mess.

Warning Order: I received a posting instruction that said in July 1967, I would be going to Tanzania. I would be working in the capital, Dar es Salaam, at the Tanzanian People's Defence Force (TPDF) headquarters. It was to be a two-year accompanied posting. I was very lucky that I could take my family with me.

Reset: When we arrived at Dar es Salaam we found it very hot but also different and attractive; after all, this was the tropics and Tanzania was prime safari land. My task was to help the staff officers with their procedures and improving their methods. The Tanzanian officers that I worked with were very proud, to the extent that they were reluctant to accept unsolicited advice. I tried to tell them where improvements could be made but, they did not want to be told how to do their jobs. As a result of their resistance, I had to come up with a new strategy. I decided to use a reactive approach rather than the proactive approach I had started with. I simply advised them that I was available for assistance when and if they felt they needed help and my door was always open to them. From that point on, when they needed help in solving a problem they asked for my help. I in turn gave them as much detail as I felt they could absorb and remained available for further requests for assistance. This strategy worked and I gained their confidence and trust by letting them use their initiative. They were keen young officers, wanting to do a good job but their pride required the freedom to be self-directed.

All’s well that ends well: Shortly after I arrived in CAFATTT I received a message from the Royal Canadian School of Signals that a Tanzanian officer cadet had failed his course. I was concerned about how this would be taken by the Tanzanian Army. So, I went to the commander's office to explain how our training system worked. When I told General Sarakikya about this student’s failure he said, "Beemer, Don't worry about this. When a man succeeds he hurts his arm trying to pat himself on the back. When he fails, he blames everyone else." I was relieved to hear his positive reaction.

Safari time: My two young daughters went to a school in Dar es Salaam. Two of the teachers were Canadian; there were children from 40 different nations in the school. So, Canada provided teachers to ensure Canadian children were accepted into school without waiting in the line-up of the other nationalities. Due to the heat in Tanzania I worked from 7:30 am to 1:00 pm. My daughters went to school at 7:00 am and came home at 12.30 pm. This meant that we could spend the afternoon doing family activities on days when temperatures were tolerable. The beach, which was on the Indian Ocean, was only 4 blocks from our house; so, we spent our afternoons swimming, snorkeling, gathering sea shells, and water skiing on occasion. We also did car trips into the countryside which was very enlightening to see the herds of animals; fruit trees loaded with monkeys eating the fruit; lions sleeping on large lower tree branches or waiting for an opportunity beside the open fields filled with large herds of many animals; and giraffes in an area heavy with trees.

Our Safety Symbol: Canada had the bull elephant as a safety symbol. On a road trip, we found out why. When we encountered elephants wanting to cross a road it was a sight to behold. The herd always stopped at the edge of the road and the bull would look both ways to make sure it was clear. If it was clear, he would cross the road and the herd would follow him. It was fascinating to see their intelligence at work; somewhat like watching children at a school crossing under the supervision of a crosswalk patrol person. This is no doubt the origin of the Canadian safety symbol used in CAFATTT.

Summary: We had a very enjoyable time in Tanzania. We travelled to Kenya and whatever countries we could reach at every opportunity. It was a memorable tour, somewhat like being on a prolonged safari, and very educational for all of us.

ANNEX B: A testimonial on CAFATTT by Al Currie (Captain retired)

My Role: On arrival in Tanzania my role, as a radio operator sergeant had not been clearly defined. It was clear that I wasn’t needed at the classroom level since the Tanzanian staff had been adequately trained for instructional duties. Our predecessors, the British, had developed a prescribed curriculum before Canada became involved and my Canadian predecessors had refined it. It therefore became clear that my role should be purely as an advisor. My boss, Major Dave Bewley, agreed.

Problem solving: Both major Bewley and I worked with the Tanzanian training staff on all levels of training including field exercises and in the classroom. I visited all battalions working through their signals officers to evaluate and solve signals problems. On field deployments I worked closely with Larry Hooper on the technical side. As one example, there had been a problem with charging NiCad 12 volt batteries at the detachment or sub-unit level. These NiCads were used in their field pack radios. Normally, these batteries were charged either through a vehicle mounted radio adaptor kit, in which these radios were installed, or were transported back to Battalion Headquarters to be charged using charging facilities there. However, the problem was that the back packs had been dismounted and dug in; they were some 30 km from their vehicle mount. In addition, the vehicle mountings could only charge one battery at a time. The alternative was to transport the batteries to Camp Magi Magi which was some 60 kilometers away. Neither solution was effective or practical. So, the battalion had some 6 volt lead acid Hart batteries which we charged, using 30 volt chargers, and transported them back to the platoon level. We then used those batteries to charge the 12 volt NiCad’s. As awkward and temporary as it was the solution suited the situation in the absence of charging facilities in situ.

Teaching Teletype: My last assignment was to set up and run a teletype operator’s course which would be the first time that teletype had been used by the TPDF. There was no hardened classroom space available so, I set up 3 tents to simulate a Tape Relay Center (TRC) and two outstations. There were about 10 students and all were experienced operators. The first priority was to get them using all 10 fingers for typing which went reasonably well. They couldn’t type very fast but they did use all ten fingers and, as we know, they would get faster with practice. When they had achieved a reasonable level of typing proficiency, I had them perforate messages on tape in their outstation tents. To simulate electronically sending the messages from their outstation tents they would physically walk their perforated message tapes to the TRC tent. When they got to the TRC, they would perform the TRC operator’s’ functions of receiving and routing tapes to their destination. Finally they would walk the tapes to the receive outstation to simulate sending them electronically from the TRC. Again at the outstation they would feed the tape into the receive station’s TD (Transmitter Distribution) head and print the message on the printer for delivery. At each stage the messages would be appropriately logged in and out as per standard message center procedures. As simplistic as this step-by-step exercise seemed, it worked; in the end, the students were proficient in the process. At the completion of the course, the equipment was dismantled and relocated to the actual stations where it became operational.

Cultural Exposure: Working in Tanzania was the experience of a lifetime. Larry Hooper and I were in a coastal town along the Mozambique border. The cultural exposure was fascinating. For example, we watched some local dancers doing a traditional tribal dance. The dancers were going in a circle, gyrating and rolling about while an old woman kept feeding them some kind of drug. It was something to see. Quite primitive and a reminder of the incredible gap between the evolutionary state of this land compared to the modern society of Canada.

Later in the day, when we were parked in town doing some people-watching, we witnessed an Asian teen on a bike get hit by a van. The driver of the van immediately took off and seemed to be running away. We asked our Tanzanian driver if we should go after him. Our driver explained that the driver of the van was not running away but, running to the police station for protection. It would not be unusual for the relatives of the teen to kill the driver in an act of vengeance. The teen had hit his head on a cobble stone with a thud which sounded ominous and final. When the police arrived they, somewhat brutally, just threw the teen into the back of the truck and drove away. This compared to, let’s say, the paramedics and police arriving on the scene of an accident back home. That was shocking to see and it put the Canadian perspective on the value of life into context Vis-à-Vis life on the African continent. On the way back to camp Maji Maji we stopped to see a leper colony. As horrible as that disease is, it was eye opening and made us thankful for the privileged, rich and healthy lives that we live in Canada.

Understanding the difference: As an example of the educational state of our Tanzanian charges, while on a radio exercise, I listened to a student giving a “Time Check” on the net which, as we know, has a prescribed radio voice procedure format. His voice procedure was perfect but the time was not even close to being accurate. I asked the Tanzanian instructor what was up with that. He explained that this student could not actually tell the time. He was doing this as a matter of procedural rote and the time seemed to be irrelevant to him. This was because in Africa, in the rural locations and with certain tribes, the only time that matters is the position of the sun in the sky. Everyone wakes up with sunrise and goes to bed with sunset and they know where they are at a given point in a day by the position of the sun.

Cultural Fauxpas: Finally on the cultural aspect, on our last night out on a convoy trip, I gave our cook a canned ham to share. Big mistake, fully half of the Tanzanians were Muslim. This emphasizes the importance of paying attention to those cultural briefings that we are given prior to our departure on foreign tours and to keep the main points in mind at all times so as not to inadvertently insult or offend the indigenous people wherever we are.

Our Volleyball Court: When I arrived in Tanzania, we were still in the early stages of our mission so our amenities had not been completely established. As we all know, one of our favoured athletic pastimes in the military is volleyball but, we did not have a volley ball court. Being the can-do-make-do soldiers that Canadians are, we grabbed a couple of shovels and started digging into the side of the hill beside the entrance to our dining room. Our Engineer Sergeant got some more shovels and soon all Senior Non Commissioned Officers were digging until we finally had a flat surface. Larry Hooper finessed the job by wiring up some lights so we could play at night. This facility provided many enjoyable hours of entertainment during our tour. Together with everything else volleyball kept us fit.

Problem Solving II: The Tanzanians had been provided with some Chinese High Frequency (HF) radios; I think we had 4 of them. They appeared to be a copy of the ANGRC 100. This is an old HF set that had about 100 watts output. Since the Tanzanians only had technical and operating manuals in Chinese, I went to the CIA storefront office in downtown Dar es Salaam and asked them to get me copies of the original documents since the radios were originally made in the USA. A few weeks later I got a phone call saying they had a package for me. The Americans are a wonderful resource when it comes to military supplies and they are always willing to help. With these manuals in hand, we then put two of these radio sets into service and used the remainder for spare parts. Talk about can-do-make-do?

Understanding the Environment: To illustrate an environmental issue, in the rainy season we used a prison farm south of Morogoro to conduct field training exercises.- Morogoro is a city with a population of 316,000 in the southern highlands of Tanzania, 169 kilometers (105 mi) west of Dar es Salaam; Morogoro is the country's largest city and commercial center. - We had allocated radio detachments to simulate a battle group and a rear link back to the Tanzanian Military Academy (TMA). We did not have antenna masts so we relied on field expedient antennas which we rigged in tall trees.

When we did our reconnaissance for this exercise there was one obvious location that met our requirements but, our Tanzanian reconnaissance officer just kept driving past it. Finally, I talked to his Sergeant who told me he had been avoiding it because of the snakes. This was a bit of an “aha” moment for me. In the rainy season the snakes like dry ground which is usually high ground and coincidentally was also where this potential headquarters site was. We then asked the officer what he thought of the obvious site that he kept passing. When faced with logical and technical considerations he deferred and agreed it was the right choice.

We cut the foliage short with what I would call African Lawn mowers to minimize refuge for the snakes. These African Lawn Mowers were like a golf club with a blade on it; sort of a mini scythe. We put out marking tape and made camp. As it turned out, the Tanzanian officer had a valid point. We found four snakes at that site which kept us on our toes, particularly given that some snakes in Africa are poisonous. The most worrisome snakes are the mamba family, black and green, which are lethal if an antidote is not given within twenty minutes. Then there are the constrictors like the python. There are 20,000 deaths annually in East Africa from snake bites. For interest read here: http://www.livescience.com/43559-black-mamba.html

BOQC: One of the courses that we provided advice and assistance to was their Basic Officer Qualifying Course (BOQC). This course had evolved from training that had been previously conducted in different foreign countries each of which were given to unique and different standards; the countries were Russia, China, Cuba, East Germany, and Canada. So the object of this particular course was to standardize their training and get everyone on the same page. A Canadian officer was the course conducting officer and he was good. The last part of this course was night patrolling. This was done in Monduli Game Park west of Arusha, and there were lots of animals. Monduli is one of the five districts of the Arusha Region of Tanzania. It was named after a wealthy Maasai in the 1880s. Monduli holds a wide variety of animals such as the Grant gazelle, gerenuk, lesser kudu, bushbuck, fringe eared oryx, leopard and lion, Thomson gazelle, dik-dik, zebra, wildebeest, ostrich, impala, klipspringer, eland, steenbok, jackal and baboon as well as the beautiful striped hyena. In the mountains there are also suni, East African bushbuck, red duiker, buffalo, bush pig and Chandler’s mountain reedbuck.

Wondering where the lions are: It was normal to go to sleep listening to the lions roar. To combat the snakes we were advised to walk with heavy feet which causes a vibration; snakes can’t hear but they do feel the vibration of human footsteps. Fortunately, none of us got snake-bit. We did run into lions and rhinos but they just wandered off. I often think of how ironic it was that here we were, Canadians teaching Africans night patrolling in an African Game Park. Nevertheless, I learned a lot from the Tanzanians. Our civilian friends would pay a fortune to experience a “military safari” such as this. It was an invaluable and treasured experience from both the professional and personal aspects.

Kilimanjaro: A highlight of a tour in Tanzania is to climb Mount Kilimanjaro. I joined a team of 10 others to climb the highest mountain in Africa and the tallest free-standing mountain in the world. It is really an endurance walk of switchbacks, arriving at a glacier on top. Kilimanjaro is a giant dormant volcano with a peak altitude of 19,330 feet. We did it without oxygen which is a bit of a feat given that oxygen is normally required above 10,000 feet in aircraft; some of the 10 climbers had tried it before and didn’t make it. Not to put too fine a point on it, altitude sickness is not to be taken lightly since it can be lethal as we have seen in the press vis-à-vis Mount Everest. One must be very fit to attempt this climb without oxygen for that reason.

The last leg of the climb starts at 15,000 feet and goes to Uhuru Peak which is the summit as seen in the diagram in the main document. I reached the summit with no problem and planted a small Canadian flag with everyone's name on it; the picture of my hand holding the flag was on the front cover of the Canadian Military magazine called the Sentinel in 1968. The third secretary to the High Commissioner of Canada and his wife were part of the team of 10. He was a former professional football player. Even he came down with altitude sickness and didn’t make it. On the other hand, his wife, being very petite at 90 pounds, actually made it to Uhuru Peak which clearly shows that size matters I suppose! I am sure that her success and his failure made for some interesting conversations around their dinner table.

ANNEX C: A testimonial on CAFATT by Larry Hooper, Foreman of Signals

Getting there: I was posted to the Royal Canadian School of Signals as the Chief Terminal Equipment Technician upon completion of the Foreman of Signals course on 9 August 1966. Another graduate of the course, Sergeant Bill Bagyan, was posted to CAFATTT on an emergency basis as Staff Sergeant John Templeton had to return to Canada, unexpectedly. Bill didn't want to go, so I told him I would go. Half an hour and two telephone calls later I was going to Tanzania! Bill was quite happy until they told him that he would be my replacement! I arrived in Dar es Salaam on 11 September. This was the ideal time of the year to go to Tanzania as the local temperature was around 30⁰C, and winter was about to take over!

My Introduction: As John Templeton had left about a month before I arrived I had go in blind. Fortunately Sergeant Bill Owens, and Sergeant Bill Fleet took me in hand and I was soon into the thick of things. When my tour was about to end I asked for, and received a one year extension to my posting. Bill Bagyan arrived at this time so we were both there for the next year. Bill was responsible for technician training while I worked in an advisory role.

The Job: My main duties were overseeing the introduction of the British Army A13 HF AM portable and mobile radios into service, setting up and equipping a communications base workshop and setting up workshops for the three TPDF infantry battalions.

Growing Pains: The A13 radio became my worst problem. We received 106 of them and they all had to be checked out before they were paid for. I found problems with about 90 of them! Plessey, the manufacturer, sent a technician over to look at the situation and he spent six weeks getting them to work! After that they worked fairly well. I prepared a list of test equipment that we needed to keep the radios working and it took about a year for it to arrive. It seems that "poli poli" (go slow in English!) was the order of the day at the time.

Dunkin Land Rovers: At about this time the TPDF received a shipment of military Land Rovers equipped with A13 radio kits. While they were being unloaded from the ship they arrived on, one of them was dropped into the harbor. It was quickly pulled out of the water and thoroughly hosed down. I thought we would have a lot of trouble with salt water corrosion in it, but the dock workers knew what they were doing and it never gave us a problem.

Field Exercise: The next operator’s course was trained on the A13 radio. At the end of the course a radio exercise was to be held and somehow I ended up sort of running it. We set up a control station at Lugalo Barracks and sent four detachments in land rovers out into the field. The radio detachments moved around a lot and one detachment was about 125 miles from the control station. We were using whip antennas on the move and dipoles when stationary.

It Pays To Bring Your Own Rations: Not everything went smoothly during the exercise. I had my own Land Rover and a TPDF technician with me. One detachment reported snakes in the area so we went there. We didn't see any snakes but the chai (strong, sweet tea) was pretty good! From there we went to another detachment which was being bothered by lions. We didn't see any lions and decided to spend the night with them. One member of the detachment was tasked with starting supper. He poured rice into a wash basin, added water, picked up a shovel and headed into the bush to relieve himself. When he came back he started kneading the rice in the water. It started to turn blackish, so I dug into my own personal cache of rations for supper!

Frequency Assignment: It seems like all of Africa communicates by HF radio! Our communications started to falter after it turned dark. We could only reach one of the TPDF stations thanks to the heavy interference we were receiving from other stations. I tuned over the band and everywhere there was interference! Finally, I found a frequency that was clear. I called the one TPDF station I could hear and told them to pass the word to the other stations to go to the frequency we had found. We soon had the net up and running again. I was highly impressed as these were newly trained operators and they were doing everything right! The next night the operators didn't blink an eye when communications got bad they quickly found a clear frequency and moved the net to it! Frequency assignments and spectrum control would come later!

Snake Bite Kit: At the beginning of the radio exercise I was issued with a snake bite kit. It contained a huge hypodermic syringe and two bottles of serum. One was for poisonous snakes and the other for venomous snakes. The instructions in the kit were in Russian, although the words "Keep Refrigerated" were printed in English on the serum bottles I asked how I was to identify poisonous snakes from venomous snakes, and was told to give a shot of each to the victim. I then asked if that might kill him. I was told this was a distinct possibility but on the other hand it might also save his life!

Spying, NOT!: The TPDF was given twelve T-54 tanks by the Chinese. They did not have radios in them, nor was there any space provided for radios. I spent the best part of a day figuring out where we could put a radio! The next day I started to finish the job but a TPDF officer told me I was not allowed as the Chinese thought I was spying on them! About a month after I returned to Canada I was called to an office in NDHQ where I was questioned about the tanks. It appears that there was concern that the Chinese had developed their own model of the T-54 tank!

On another occasion I was taken to a storage area where a number of Russian military radios were being kept. A day or two later I was told to forget I ever saw them as the Russians were upset about my visit!

Buying Field Radios: I was reading an American radio communications magazine and noticed an ad for the Harris RF-301 vehicular synthesized HF SSB radio. The US navy was using it in their river patrol boats in Viet Nam. I wrote the company and requested more information. Two weeks later a representative of the company showed up and wanted to demonstrate the radio. We took it to the communications centre and set it up. It worked extremely well and was easy to operate. Without further ado the TPDF ordered four of them! They arrived several months later and we used one as the net control station on the TPDF net. We installed the other three in Land Rovers. The antennas were 12 foot fiberglass whips and they were very stiff. On our first test drive the antenna hit some tree branches and tore the antenna mounting bracket off the vehicle! The TPDF mechanics were quick to come up with a reinforced bracket!

Test Equipment: All of this new radio equipment required better quality test equipment than the TPDF then owned. I suggested that new test equipment was required and submitted a detailed list. The list disappeared somewhere but the test equipment, oscilloscopes, signal generators, spectrum analyzers, etcetera, showed up about four months later.

Fixed Communications: Captain Yerxa and I were asked to prepare a plan for a new fixed communications system for the TPDF. The main station was to be at TMA - once they put up a building for it. We wrote a detailed specification for a SSB voice/RTT system. As far as I know, Rhode and Schwartze from Germany was the only company to submit a bid. Shortly after this I returned to Canada on leave. While at home I received a letter from Rohde and Schwartze asking me to visit their facilities on my trip back to Tanzania. I did this and met Dr. Rhode and Dr. Schwartze (whom I had already met earlier in Nairobi). The visit was fascinating as Dr Rhode showed me just about everything they were working on for future HF communications. I was also shown a guest book signed by Adolph Hitler, Heinrich Himmler and several other Nazi notables! I understand that a contract was later signed but this was after I had returned to Canada.

We were asked to plan a temporary communications facility at Lugalo Barracks to be used until the new building at TMA was available. The idea was to build a radio room with five operating positions using the old but reliable HF150 SSB transceivers that fed Rediphone 500 watt linear amplifiers. A second room housed the teletype equipment and a signal center. Each amplifier consumed about 1500 watts of power and the radio room soon became a furnace. An air conditioner was installed and the building soon became everybody's favorite place to be! I left Tanzania before this project was completed and my replacement Sergeant Al Palmer finished the job.

We needed cabinets in which to install the radio equipment. None were available so a local metal shop was contracted to design them. They did a pretty good job on the cabinets but screw holes for securing the equipment panels were improperly spaced. We had to drill new holes! We also needed antenna towers and again, none were available. We did some more drawings and another metal shop built them. They did a nice job excepting that the holes on the tower mounting flanges would not match up. We spent a day re-drilling the holes which normally would not have been much of a job. However, in Africa the ants (they are all red and bite anything within reach) kept on crawling up our legs. We had to continuously "mark time" while we were drilling the holes and assembling the towers! Our Royal Canadian Engineer Sergeant brought over an Armoured Personnel Carrier and a crew of TPDF engineers and they put the towers up in a couple of hours.

Summary: My tour in Tanzania was the most challenging job I had in the CF. I think I learned a lot more than I contributed. The people I met were friendly and helpful, and they learned many things quickly.

ANNEX D: A testimonial on my tour in Tanzania by Gerry Watt

Introduction: In mid-1967, while I was in the Air Support Signals Troop, at the Canadian Joint Air Training Centre, in Rivers Manitoba, I received a posting instruction posting me to CAFATTT. There were no details so I had no idea what my employment would be. I went through the normal administrative and medical clearance procedures for an overseas deployment including the mandatory inoculations. Several months later, in April 1968, my travel instructions came in and I was on my way. The first stop was at National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa where I was briefed as to the purpose of my tour. The major to whom I reported pointed to Dar es Salaam on a map and said that is where you are going. Your mission is to conduct the first Group III Radio Operators’ course for the Tanzanian People’s Defence Force. That sounded interesting and challenging to say the least. But, I had assumed that the necessary infrastructure, guidelines, tools and instructions were in place and that all I would have to do would be to step into a classroom and start talking; after the necessary planning and preparation of course.

Getting there: After doing more departure administration in Ottawa I was presented with a return air ticket. I departed on a BOAC flight to London Heathrow arriving in fog early in the morning after a long overnight flight. From Heathrow, I went, via a double decker bus, to catch an East African Airways flight at Gatwick airport. At Gatwick, I boarded a new Super VC-10 which impressed me to say the least. We flew to Paris France, Athens Greece, Entebbe Uganda, Nairobi Kenya and ultimately Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. I was met by Sergeant Frank McDonald with the Keko flats van.

Arrival: After settling into my room, and having a good night’s sleep, I was given a tour of the facilities the following day. The facilities were far more primitive than I had envisioned! I was replacing Sergeant Al Currie who was still there. He gave me a tour of his classroom, which was a tent, where he was instructing a course on teletype. My expectations were lowered considerably; my visions of grandeur had become my delusions of grandeur.

My Task: It was about this time that I discovered the true magnitude of my task and it was unnerving to say the least. I had to prepare a complete group III radio operators’ course from scratch and be ready to go in 6 weeks. Nothing had been prepared for me. To say that this would be an onerous task would be the understatement of my life. I had all of a sudden become the Chief Instructor, Standards Officer, Course Training Standards writer, Course Training Plan writer, Course developer and class room instructor all in one. On the other hand, I had a license to kill so to speak. I could determine from my own experience what was important for these people to learn at their group III level. The bottom line is that I did it. I developed a plan and stuck to it except for a minor alteration after the first week.

Teaching Morse Code: A major challenge was teaching Morse Code. I had not been a fan of Vimy Code Voice, the method used to train Morse Code in Vimy back home. Instead of starting at 6 words per minute like Vimy Code Voice, I instructed them by keying the letters, numbers and prosigns at 20 words per minute with large spaces in between characters. I also used beat music in the background to give them a sense of cadence. Over time I gradually decreased the spacing between letters as they progressed in ability. Within six weeks they were doing between 18 and 20 words per minute. They loved the beat music and Morse Code became music to their ears.

Reset: A week into the course and I had to stop and revise the course since these students obviously lacked some important background knowledge, like basic arithmetic. So, I added a two week course on arithmetic at the beginning so they could calculate antenna lengths! I was told there will be NO failures at the end of the course.

Innovation: Due to the absence of training aids, some creativity was required. So, during a theory period on magnetism, I created a training aid using an old metal ashtray, some wire, a motorcycle battery and a hand full of spikes. I wound the wire around the spikes and asked a student to hold each end of the wire on the two terminals of the battery to energize the magnet. I held the magnet over the ash tray and the ash tray slammed up into the spikes. That reinforced the students’ idea that everything was magic. Probably not a good idea given their state of development!

Field Exercise: To confirm their classroom training, we went to the Arusha area for a field exercise conducted by Capt. Doug Yerxa. In order to simulate a headquarters we had a Land Rover with an RF 3 01 and a 42 set installed in it. We had another Land Rover with a switchboard installed in it with several lines laid out to simulate deployed units. Two of these lines were over a mile long laid on the ground.

The student mentality in Tanzania was not the same as our students. To illustrate the difference in mentality, I had instructed the switchboard operator to check those lines once an hour to ensure they were still serviceable. In the morning I saw this young fellow walking toward the switchboard truck with a wire in each hand. I went over and asked him what he was doing. He said, “Bwana, I was checking the lines once an hour as you had asked.” He had obviously misunderstood my instructions and I had failed to ensure that he understood. So, I showed him how to check the line using the key on the switchboard which I should have done in the first place; I showed him that If the light came on when he pushed the key up that indicated the line was OK. With this explanation he said, “Don’t tell me that Bwana - don't tell me that”. He had been walking back and forth all night with a wire in each hand checking the lines; it was about a mile each way! Other than for a rhino chasing the Tanzanian Army off of the field the exercise was routine; the rhino was just trying to find someone to butt heads with I suppose!

A real bed: At one point during the exercise, we went into Arusha and stayed overnight in a hotel to have a shower, some real food and a real bed - John Wayne had stayed there making a movie which made the stay somewhat exotic. That was a refreshing break; the liquid refreshments were just what the doctor ordered to clear the dust from our throats.

Touring: My tour in Tanzania was not all work. Captain Doug Yerxa and I went on a safari to Ngorongoro Crater, in one of our Land Rovers, with four TPDF soldiers. The Ngorongoro Crater is an extinct volcano that collapsed on its self over 3 million years ago. The height of this volcano would have rivaled Kilimanjaro at over 5,800 meters before it erupted whereas its floor is now about 1,800 meters above sea level. It must have been one hell of an explosion when she blew. The crater measures up to 19 kilometers across and has an area of 264 Square kilometers. It contains part of the Serengeti, the Olduvai Gorge where the Leakey’s discovered the skull of Homo erectus among other ancient artifacts and the plentiful wildlife that the Serengeti itself is noted for. It is a significant African tourist area with many tourist resorts and is probably the place to go for an African safari. The crater lies some 120 Kilometers west of Arusha.

Ngorongoro Crater: Our trip to the Ngorongoro Crater was in July and the young soldiers were from a coastal Tribe. They had never been inland to the high ground. Captain Yerxa and I had worn our parkas so the young fellows had thought we were a bit strange. They were in shirt sleeves which of course was good for the lower elevations! But, by the time we got to the lodge at the crater’s rim we were at 8,800 feet above sea level. It was cold and they were freezing. They did not think we were dressed so strange any more. So Captain Yerxa and I gave them our parkas; we gave the parka shells to two of the soldiers and the parka inners to the other two. Now we were in shirt sleeves and we were freezing. We went down into the Crater where it was much warmer and stayed there until between 5 and 6 pm. They had never experienced anything like it especially the cold. We got our parkas back when we got back to camp.

Kilimanjaro: Later in my tour I climbed MT. Kilimanjaro. The climb took 5 days, three days up and two days down. It was a great adventure but, my predecessor, Al Currie, has described this trek in his testimonial so I will defer to his version of events. Suffice it to say climbing Kilimanjaro was an experience of a life time because it is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain in the world.

Sailing: One of the local pastimes in Dar es Salaam was sailing. I became a crew member on a Lightning class sail boat. We raced Wednesdays and Saturdays and were known as the bomber crew because of the old RCAF May West life preservers we wore. We even managed to win a few races after we got our act together. A Canadian professor at the University of Dar es Salaam owned the boat. Incidentally, I took a six week course on Swahili at the university but I was far from fluent at the end.

The Chinese army was teaching anti-Aircraft artillery to the TPDF in our area. One of their young instructors was indoctrinating them by teaching Mao’s thoughts from Mao’s red book. For fun, I would join them with my red covered English dictionary. The locals used to roll around on the ground laughing at me. It became a bit of a contest because the Chinese were our rivals and they won out in the end. I surely tortured him but he took it all in good humour and we had a good rapport. When his bosses weren't looking I helped him to fix stuff that broke because he didn't have a clue. At the same time, he was fluent in Swahili and I was not. All of that said, the day that I left to return to Canada, he was there waving to me. God bless the young man. I hope he has a long life. In the final analysis, I think we could learn something from the Chinese. They were given a two year course on Tanzanian language and culture to prepare them for their time in Tanzania. We were at a distinct disadvantage to them given this cultural education!

Summary: To sum up, the course was successful. All 14 Tanzanian students passed as directed. I was proud of what I had accomplished and I can truly say that my tour in Tanzania was a highlight of my career. I would do it again in a heartbeat.

ANNEX E: A testimonial on CAFATTT by Carl J. Arthurs (Master Warrant Officer Retired)

Warning Order: In 1966, while I was stationed with 711 Communication Squadron in Canadian Forces Base Valcartier, I was posted to Tanzania with CAFATTT. Prior to going overseas, I moved my family to Saint John New Brunswick and proceeded to Tanzania in June 1966.

Arriving in Tanzania: When I arrived at the airport in Dar es Salaam I was met by Major Potts, whom I knew from Hanover Germany when I was with the 27th Brigade, and Sergeant Bill Fleet who I was replacing. Bill and I had arranged a two week handover; as a result, I was not flying blind which, unfortunately, had been the case too often with other members of CAFATTT.

African Architecture: The building we used as an Office, Classroom and Workshop had two rooms, a tin roof and openings for windows (no glass just dropdown shutters which is common in Africa) and a walkway in front with overhead protection from the elements.

Can Do, Make Do: Sergeant Bill Bagyan, who I was assisting in teaching Basic Electronics, had a very basic diagram for a circuit tester but there were no training aides. So, we cannibalized some old 19 sets and other surplus electronic apparatus for parts that we could use to produce some training aides.

Buying Teletype Equipment: In the classroom I was not able to teach specific equipment because the TPDF had not yet decided on the equipment that they were going to purchase. So, I taught basic teletype theory in preparation for the inevitable arrival of whatever equipment was purchased. On that score, we were still talking to the representatives from the Creed and Siemens Companies to establish which devices we were going to recommend to the TPDF. During this process, I began to experience some of the lobbying techniques that industry uses to motivate governments to choose their products. This gave me a mini appreciation for what the major equipment acquisition project offices in National Defence Headquarters must experience when buying equipment such as trucks, airplanes, ships and communication systems. The pressure was on me as the so-called resident expert in crypto and teletype equipment to make the choice between Creed and Siemens equipment; “I was a one man project office”.

To be fair, objective and honest, I turned down offers of Dinner on two occasions and a free long-weekend trip to Victoria Falls which were offered by the company representatives; Victoria Falls is in southern Africa on the Zambezi River at the border of Zambia and Zimbabwe. The brutal truth was that I knew I would have to give the TPDF my assessment that the Creed equipment, as I knew it, was not suitable for the future plans of the Communication system for the TPDF. Obviously, it was recommended that the TPDF buy the competing Siemens teletype equipment.

Crypto: The Cryptographic equipment that was recommended and purchased was a Manual Cryptograph Machine that was made in Switzerland. The day it arrived I was asked to stop by Army House and meet with Lt. Kabogo to check out the new equipment. He asked me to take one of the pieces of Crypto Gear back to the Quarters in Keko Flats and work on some procedures. Of course I politely declined and explained to him how Cryptographic equipment should and must be secured and protected. It was clear, at that point, that the TPDF had a long way to go in building effective and competent electronic communication capabilities.

Departure: On my departure from CAFATTT I was replaced by Sergeant Ken Quigley. We did not have the luxury of the handover period that I had with my predecessor. So, I left Ken a folder with a list of what Bill Fleet and I had accomplished and what he could expect in the future.

Summary: On returning to Canada I was posted to Debert, Nova Scotia. As I look back I remember my time in CAFATTT as frustrating which can be the case when building any organization from scratch without the benefit of a clear plan to follow or the resources needed. The entire tour was a test of my ingenuity, imagination, initiative and resourcefulness. Regardless, I am very pleased and happy to have had the experience and I would do it again. In the final analysis I came away from that experience with a new awareness of how privileged I had been having served my career in a well-established and professional army.

ANNEX F: A testimonial on CAFATTT by Bill Fleet (Master Warrant Officer Retired)

Swahili: I was posted to the Canadian Armed Forces Advisory and Training Team in Tanzania (CAFATTT) in January 1966 and arrived in Tanzania in May after attending a six week crash course in Swahili. As one would expect, the course was really just an introduction to the language giving us essentially useful phrases and terminology to use. We were by no means fluent in Swahili at the end of that training. It was interesting to learn some of the language but, on arriving in Tanzania, I found that all conversations were in English anyway. That is not to say that the Swahili course was a waste of time. On the contrary, I was able to use all that I learned at one time or another.

Arrival in Tanzania: I arrived at the airport in Dar es Salaam with two other Canadian Forces personnel. We were met by a welcoming crew and we were transported to the barracks at Keko Flats and my home for the next year. My accommodation at Keko Flats was an apartment which I shared with another team member. The apartment was adequate but only cold showers were available which provided an exhilarating start to each day.

My New World: My primary duties were to establish a teletype maintenance workshop and to teach the Tanzanian students teletype maintenance and fault finding. The workshop was set up in a cement and mud hut which had “paneless” windows (no glass). In lieu of glass there were shutters in the window frames which are common in Africa because the warm climate dictates maximum ventilation for comfort. Our quarters were the same as the married quarters that were occupied by the Tanzanians and were collocated with them and near their latrine. Each morning the Tanzanian ladies would bring their children to the latrine for their morning wash in a long trough positioned under taps that provided very cold water. It was a noisy affair because the little ones didn't enjoy their cold baths but the moms scrubbed them clean anyway. I can’t say that I blamed the little ones for objecting to the cold baths.

On The Job Training: The demonstration teletype that was being used at the time that I arrived in Tanzania was a Creed model 75. It had been stored in a Quonset hut for an extended period, in high humidity which, as one can imagine, was hard on the metallic components. So, the equipment was in bad shape. Once repairs and clean up of the equipment was complete I set up a network linking a couple of model 75s so that the students could get hands-on practice working on them. The students had a challenging time with the equipment due to frequent breakdowns. Ironically though, the frequent breakdowns were a good thing given that they presented many opportunities for the students to do fault finding and repair. The students were very eager to learn and they were enthusiastic about the opportunity to practice their new found skills. That said, the students were housed in tents without the benefit of electricity so studying from the textbooks each evening was not possible. But, this was Africa after all so we simply adapted our training to the conditions.

Bats’n Bugs: From an environmental perspective, bats are ubiquitous in Africa. As we know, bats are nocturnal so, in the evenings at dusk the bats came out in swarms. This often resulted in a nightly bat infestation in the workshop due to the “paneless” windows. Getting the bats out of the workshop was always a bit of a challenge because their inherent “sonar/radar” detects all objects in their path and they effectively evade any object being put in their way. A long thin stick was the most effective tool to chase them out with which we learned from the Tanzanians. The long thin sticks presented the smallest profile to the bat’s “radars” which made them vulnerable.

Insects are also plentiful in the warm and humid central African climate. When I returned to the workshop after a long weekend I discovered that termites had eaten the wooden leg off of a work bench; burrowed a path through the training manual; and gnawed all the paint off of the key generator. The Tanzanian maintenance crew quickly repaired the work bench but not much could be done about the tunnel through the training manual.

Replacing the Creed Model 75: Given the frequent difficulties with the model 75 teletypes it was decided to source alternative equipment. I wrote to Teletype Corp in the US to inquire about their model 15. Disappointingly the model 15 was no longer in production. The alternative then was Siemens equipment but no decision had been made up to the time that I departed Tanzania. The resolution of the Creed model 75 replacement problem was therefore left in the hands of my capable replacement, Sergeant Carl Arthurs.

Souvenirs: During my free time I enjoyed going to downtown Dar es Salaam. On one of these sojourns I found talented tailors who made great men's shirts and nice dresses for the ladies that we could take home as gifts; hopefully the right size! There were many other choices for the gifts that soldiers like to take home at the end of their foreign tours. Among them in Tanzania were wood carvings and paintings. But, there was no need to go into town for these things since the local Tanzanian artists would frequently bring their wood carvings and paintings directly to the mess where we could “shop at home”. My family members have Tiki paintings and carved mahogany masks on their walls to this day.

Sharing: We were able to share a little bit with the locals. On occasion, Canadian Forces Headquarters would send us care packages to help us celebrate a Canadian holiday. There was nothing that we really needed so the care packages were given to the Medical Officer who would distribute these gifts (canned ham, vegetables, candy, etc) to the local orphanage in Dar es Salaam; hopefully the orphanage kept the canned hams away from the Muslim children! Also, at Keko flats, we had movie nights with movies that were provided by CFHQ in Ottawa. We viewed the movies outside on a large white wall so our Tanzanian neighbours always joined us for movie nights and enjoyed themselves. Many of them had never seen a movie before. We also shared our soccer ball with the local children who played soccer daily. We tossed the ball to them in the afternoon and they threw it back to us in the evening when they were done.

Summary: In summary, my experience in Tanzania was fun and memorable. I would even call it a highlight of my career. My replacement, Carl Arthurs, and I had a two week overlap so we could do a good handover which provided some essential continuity. I enjoyed working with Carl again and I knew that my workshop and my students had been left in capable hands. After spending the mandatory week in the National Defence Medical Center in Ottawa, to make sure that I had not contracted any exotic tropical diseases, I moved my family to Debert, Nova Scotia.

See Also

References

- ↑ Story courtesy of the Semaphore-to-Satellite project.